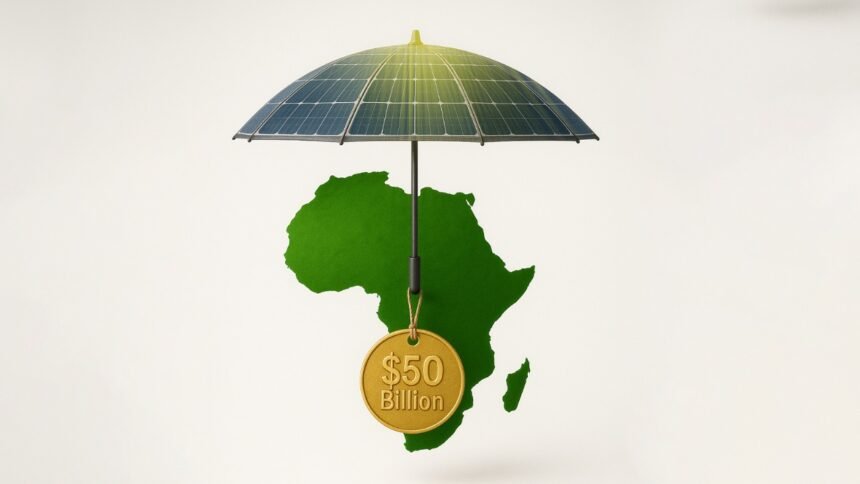

Africa is tired of playing the victim in the climate conversation. That was the unmistakable message coming out of the Africa Climate Summit in Addis Ababa this week, where leaders from across the continent announced an audacious goal: to raise $50 billion a year for a new climate solutions initiative. If the pledge sounds ambitious, that’s because it is — and the world will be watching to see whether this vision is a turning point for Africa or just another lofty promise that fades into the political ether.

At its heart, the Africa Climate Innovation Compact is designed to tackle the twin challenges Africa faces in the climate era: vulnerability and underdevelopment. The numbers are stark. Africa is responsible for less than 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions, yet it bears some of the most brutal costs of climate change — prolonged droughts in the Horn of Africa, rising sea levels along the continent’s coasts, and devastating floods in countries like Mozambique and Nigeria. African leaders have long argued that the climate crisis was not of their making, but its impact is rapidly eroding decades of economic gains. This week’s initiative marks the most coordinated attempt yet to flip that narrative and position Africa not as a victim but as a player, even a pioneer, in climate solutions.

The new plan calls for $50 billion annually — a mixture of public funds, private investments, and development finance — to fund renewable energy projects, climate adaptation programs, and green technology incubators across the continent. In practical terms, this means everything from building solar farms in the Sahel to upgrading irrigation systems for farmers in East Africa and financing climate-resilient infrastructure in coastal cities like Lagos and Dar es Salaam.

But if this is a bold vision, it is also one fraught with challenges. Raising $50 billion a year will require Africa to overcome its biggest obstacle: financing gaps. Historically, the money pledged to Africa on climate issues by wealthier nations has failed to materialize. Remember the $100 billion a year promised by developed countries at COP15 back in 2009? More than a decade later, that target is still unmet, with some estimates suggesting that actual disbursements are closer to $83 billion — and even then, much of it in loans, not grants. The Addis Ababa plan therefore represents a gamble that Africa can attract significant private capital, especially from investors eager to tap into the continent’s vast renewable energy potential.

President William Ruto of Kenya, one of the summit’s most vocal figures, put it bluntly: “We are not asking for charity. We are offering the world the greatest investment opportunity of this century.” It’s a message designed to appeal to global capital markets, and it has some merit. Africa is home to 60% of the world’s best solar resources but accounts for just 1% of global solar capacity. The potential for wind, geothermal, and green hydrogen is similarly vast. Unlocking these opportunities could transform Africa’s energy landscape, bringing power to hundreds of millions who still live without electricity while also positioning the continent as a hub for the global energy transition.

Yet, skepticism remains. Analysts warn that lofty announcements are not enough without a credible roadmap for implementation. Many African countries struggle with governance issues, corruption, and weak institutions that make investors wary. There is also the perennial problem of political instability, from coups in West Africa to protracted conflicts in Sudan and the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. These challenges could spook the very financiers Africa is hoping to court.

Still, there is reason for cautious optimism. The Africa Climate Facility, the financial arm of the new initiative, is being designed to de-risk investments, providing guarantees and blended finance mechanisms to attract private players. In addition, multilateral development banks such as the African Development Bank are expected to play a leading role in coordinating funding and ensuring that projects meet international standards.

The Addis summit concluded with applause, selfies, and high-minded declarations about Africa taking control of its own destiny. But as with all climate diplomacy, the hard work begins after the headlines fade. Will $50 billion a year actually flow into African projects, or will this end up as another well-meaning plan that never leaves the paper it’s printed on? For now, Africa has thrown down the gauntlet. The ball is in the world’s court — and if investors bite, the continent might just pull off a green revolution that benefits not only Africans but the planet itself.