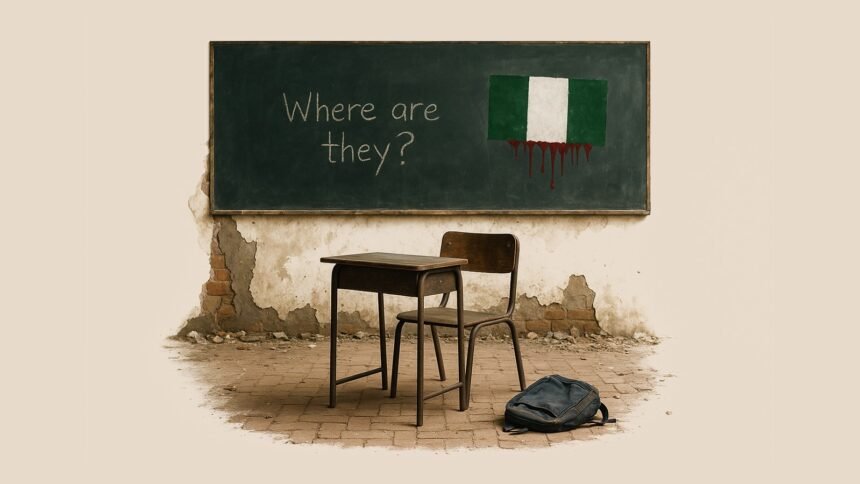

Another week, another headline soaked in horror from Nigeria’s troubled northwest. In the early hours of August 2nd, gunmen stormed the village of Sabongarin Damri in Zamfara State, killing at least eleven people and kidnapping more than seventy, including scores of children. For locals, this wasn’t a tragedy—it was a routine. And that, perhaps, is the greatest tragedy of all.

Witnesses say the attack began just after midnight. Dozens of armed men on motorcycles, their faces hidden by turbans and masks, surrounded the village. “They didn’t speak much,” said Auwalu, a farmer who escaped into nearby fields. “They just shot anyone who didn’t run.” By dawn, the blood of fathers soaked the soil of sorghum fields, and children had vanished without a trace.

This is not an isolated event. Zamfara and its neighbouring states—Katsina, Kaduna, Niger—have become Nigeria’s abduction belt. Since 2021, well over 5,000 people have been kidnapped for ransom in the northwest. Banditry has evolved from opportunistic crime to a full-fledged industry. Armed groups operate with military efficiency, targeting schools, markets, and villages. Ransom payments, often in cash or livestock, fund further raids, creating a self-reinforcing nightmare.

The Nigerian state’s response? Tepid at best, tragic at worst. Within hours of the Sabongarin Damri attack, the police issued a bland statement promising an investigation and “increased patrols.” President Bola Tinubu, speaking at a development summit in Abuja that same day, offered condolences—then shifted to discuss infrastructure goals for 2030.

No emergency visit to the affected families. No troop deployment. No aerial surveillance. In a country where bandits often have better weaponry than local police, villagers are left to pray, hide, or pay up.

The economics of kidnapping are simple. Ransoms range from $200 for a child to over $100,000 for a senior local official. Families sell farmland, jewellery, even livestock to raise funds. When that fails, communities crowdfund. When that fails, captives disappear forever.

Children taken from Sabongarin Damri are believed to have been herded into forest camps that serve as makeshift prisons. Survivors of past abductions recount weeks in chains, forced marches at gunpoint, and constant threats of execution. Some emerge traumatised. Others never return.

Zamfara’s governor, Dauda Lawal, has called for federal intervention. But Abuja’s rhetoric-heavy, result-light approach has sparked fury. “How many more villages must be emptied before they act?” asks Fatima Musa, a local schoolteacher. “Or do we only matter during elections?”

Indeed, politics hangs heavily over this crisis. Banditry in the northwest has become a litmus test for state legitimacy—and it’s failing miserably. Local officials, often accused of collusion or negligence, rarely face consequences. In some cases, they have been caught negotiating with criminal groups in backdoor deals. One leaked audio recording from 2023 featured a former governor allegedly brokering a truce with a bandit commander in exchange for “peaceful elections.”

With national security forces stretched thin by insurgencies in the northeast, separatist unrest in the southeast, and political instability in the oil-rich delta, northwest Nigeria has become the country’s most dangerous blind spot.

But there’s another element to this crisis—apathy. The kidnapping of seventy villagers, including babies and elderly women, barely registered in national headlines beyond a single news cycle. International media? Almost silent. Compare that to the global outcry over the 2014 Chibok girls’ kidnapping, and the contrast is jarring.

Why the silence? Fatigue, perhaps. Or the fact that Zamfara lacks the photogenic narrative arc that Chibok had. Or perhaps because poor rural children just don’t pull clicks anymore.

Yet for those in Sabongarin Damri, the nightmare is far from over. As families mourn their dead and wait in agony for ransom demands, their trust in the Nigerian state disintegrates further. Some are joining vigilante groups. Others are fleeing altogether. The rest just pray they aren’t next.

The deeper cost is psychological. Children now grow up not fearing monsters under the bed, but men with guns on motorcycles. Schools empty out after dark. Parents drill their kids not on maths, but on what to do if taken. The fabric of rural life is fraying, one abduction at a time.

And in Abuja, as politicians pontificate on their Vision 2030, Zamfara continues to bleed—quietly, steadily, invisibly.