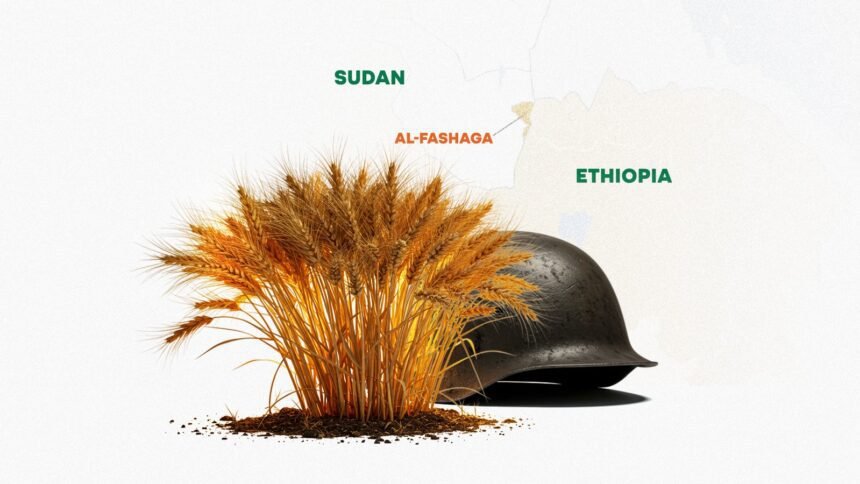

Once again, Ethiopia and Sudan are back at the negotiating table, attempting to calm one of Africa’s most stubborn border disputes before it flares into another shooting war. Talks held this week in Addis Ababa focused on the al-Fashaga triangle, a fertile strip of farmland that has been claimed, reclaimed, and fought over for decades.

Ethiopia’s Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Demeke Mekonnen opened the meeting with warm appeals for “brotherly relations.” Sudan’s acting Foreign Minister Ali al-Sadiq said confrontation was no longer an option. The handshakes looked good, but history says smiles can quickly turn into standoffs.

Al-Fashaga’s 260 square kilometres of green farmland are claimed by Sudan but long used by Ethiopian Amhara farmers, often with quiet backing from Addis Ababa. When Sudanese troops seized the land in late 2020, Ethiopia was distracted by its war in Tigray — and the resulting clashes left dozens dead on both sides. The memory still lingers.

Sudan’s political situation makes compromise risky. Its military-led government is still locked in a deadly civil conflict with the Rapid Support Forces and must look strong to its supporters. Ethiopia, meanwhile, must balance national diplomacy with local Amhara demands not to “give away” ancestral farmland. Neither side can afford to look weak, which makes this round of talks as delicate as ever.

Regional politics hover over the table. Egypt, which has opposed Ethiopia’s massive Nile dam project, has often sided with Sudan, hoping to squeeze concessions on water flow. That means any breakthrough could reshape Nile Basin diplomacy — and any collapse could open a new front in the region’s power struggle.

This week’s meeting did produce movement: both countries agreed to create technical committees to review maps and draft proposals for joint management. The African Union offered to mediate, but both sides seem to prefer keeping the process bilateral, wary of outside interference. “This is our problem to solve,” said one Sudanese negotiator.

Ordinary people just want the shooting to stop. Border towns like Gedaref and Metema have suffered through road closures, disrupted trade, and burnt-out farmland. Farmers fear losing yet another harvest to military skirmishes. “Let them settle it once and for all,” one Sudanese farmer told reporters. “We just want to plough in peace.”

A successful agreement could stabilise one of East Africa’s most volatile fault lines and let both governments focus on rebuilding after years of war. But failure could mean another cycle of attacks and counterattacks as soon as the next rainy season makes the land valuable again.

For now, there is talking instead of shooting. But if past experience is any guide, this diplomatic moment could be short-lived. Al-Fashaga has a way of turning handshakes into headlines — and headlines into gunfire.