Saharan Syncopations: Pan-African Rhythms in Ghana’s Melodic Tapestry

Across Africa’s vast sonic landscape, from the Sahel’s griot strings to the Congo’s soukous sway, music has long served as a vessel for cultural fusion and communal resilience. In West Africa, where colonial legacies intersected with indigenous innovations, genres such as highlife emerged as postcolonial anthems, blending palm-wine guitar licks with brass-band bombast and jazz improvisation. Born in the Gold Coast’s coastal ports during the 1920s, highlife mirrored the region’s hybrid heritage, Ga, Akan, Ewe rhythms mingling with calypso and swing imports, evolving into a pan-African dialogue that echoed from Lagos clubs to Dakar dancehalls. Pioneers like Nigeria’s Fela Kuti infused Yoruba beats with funk’s fire. At the same time, Senegal’s Youssou N’Dour wove mbalax into global grooves, but Ghana’s contributions anchored this movement in communal joy and social commentary.

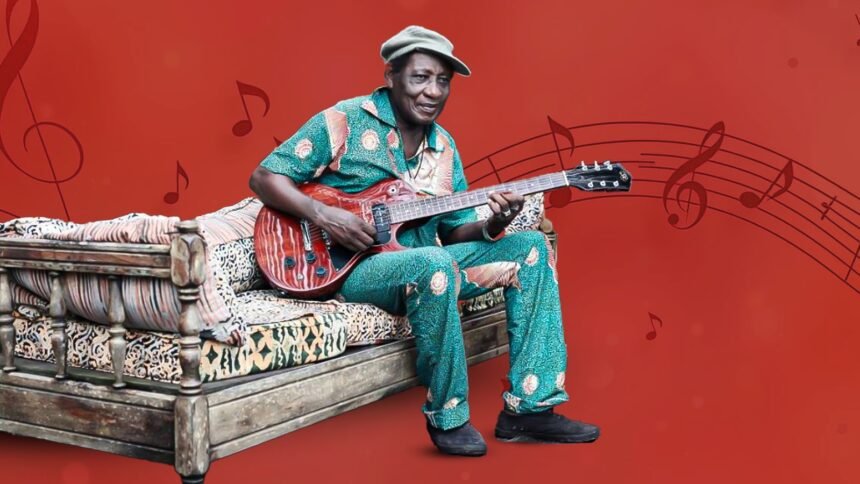

The mid-20th century amplified these echoes amid independence struggles: Kwame Nkrumah’s Ghana in 1957 championed cultural revival, highlife bands touring pan-African festivals to forge unity against neocolonial divides. Yet political upheavals, military coups in the 1960s–80s, and economic slumps threatened these traditions, prompting artists to migrate or adapt to survive. Living legends such as Pat Thomas sustain highlife’s heartbeat, while departed icons such as C.K. Mann and Gyedu-Blay Ambolley paved the way for hip-hop hybrids. Ebo Taylor, bridging eras, embodied this continuum: his guitar a conduit for Ga polyrhythms, Akan chants, and Dagomba dances, thereby influencing the spread of Afrobeat and mentoring youth in Accra’s studios. His legacy whispers to emerging voices, Black Sherif’s rap-highlife fusions, Stonebwoy’s dancehall infusions, urging cultural preservation amid the tide of globalization.

Cape Coast Cadence: Ebo’s Ghanaian Genesis and Global Ascent

Deroy Taylor, known eternally as Ebo, was born on January 6, 1936, in Cape Coast, a historic harbor where Atlantic breezes carried echoes of trans-Saharan trade and colonial conquests. Once the Gold Coast’s capital, this coastal enclave hummed with palm wine parlors and brass ensembles, birthing highlife amid British rule’s twilight. Young Ebo, piano keys under fingers by six, absorbed American jazz broadcasts and English hymns, his tastes a mosaic of empire’s imprints. Switching to guitar in college, he dove into the genre’s golden age, joining the Stargazers, a crucible for talents like Teddy Osei and Sol Amarfio, who later founded Osibisa’s Afro-rock empire.

Ghana’s 1957 independence ignited Ebo’s trajectory: highlife as the national soundtrack, bands such as the Broadway Dance Band channeling communal exuberance. In 1962, London beckoned, and the Eric Gilder School of Music offered formal training, where Dvořák’s symphonic complexities reshaped his approach. Yet, streets taught more: jamming with the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and crucially, Fela Kuti at Trinity College. Their bond, forged in highlife reverence and aspirations to emulate Miles Davis or Kenny Burrell, sparked innovations, Ebo forming the Black Star Highlife Band, infusing major-mode melodies with minor-key depth. Returning home in 1965, he led ensembles like the New Broadway Dance Band and Blue Monks, nurturing peers like Pat Thomas amid Nkrumah’s pan-African vision.

Continental Choruses: Ebo’s Role in African Musical Evolution

Ebo’s artistry pulsed with Africa’s rhythmic renaissance, highlife his canvas for blending traditions. In the 1970s, as Essiebons label’s in-house maestro, he arranged, produced, and strummed for luminaries, Pat Thomas’s soulful croons, Gyedu-Blay Ambolley’s funk experiments, while crafting solos that wove Ga syncopations with Ewe polyrhythms and Akan harmonies. Albums like Twer Nyame and Conflict Nkru! fused highlife’s upbeat brass with afrobeat’s hypnotic grooves, James Brown’s funk infiltrating Yoruba and Fante forms. His Malian grandmother’s lore added Saharan shades, creating soundscapes that transcended borders.

Collaborations amplified this: Fela’s encouragement to root music in African soil gave rise to tracks honoring Dagomba warriors and coastal chants. In the 1980s, stepping from spotlight to studio, Ebo mentored amid Ghana’s economic woes, his work sampling-ready for global hip-hop, Usher’s beats, and Black Eyed Peas’ hooks, drawing on his heaven-sent riffs. The 2000s university tenure in Ghana sowed seeds in students. In comparison, the 2010s Love and Death revival of his voice internationally, with Strut Records channeling his essence to festivals such as WOMAD and Nuits Sonores. Yen Ara and Palaver extended this, jazz infusions meeting funk’s fire, his stroke in 2018 only shifting expression, sons Henry and Roy carrying guitar duties in Jazz Is Dead’s 2025 collaboration.

Heritage Horizons: Ebo’s Enduring African Cultural Legacy

Ebo’s imprint etches deeply into Africa’s cultural fabric; highlife is his tool for preserving heritage amid modernity’s march. Lifetime awards, from the Vodafone Ghana Music Awards to the Highlife Music Honors, culminated in his six-decade reign, celebrating a man who elevated Ghanaian music globally as Western genres dominated. His festival launch, mere hours before his February 7, 2026, passing at 90, symbolized this: a Saltpond elder, “Uncle Ebo,” bridging elders’ tales with youth’s aspirations. Samples by Kelly Rowland, Jidenna, and Vic Mensa globalized their grooves, introducing Akan rhythms into urban beats, while reissues like Life Stories unearthed 1970s gems for new ears.

In pan-African contexts, Ebo paralleled Fela’s Nigerian revolution, their London jams seeding West Africa’s sonic sovereignty. His music, vibrant and inventive, countered museums’ stasis, progress rooted in tradition, as he professed. For Ghana, he was a colossus: putting rhythms on maps, mentoring in Accra’s academies, fostering unity in diversity. To successors like Black Sherif, his solace: witness greatness, carry the cadence. Ebo’s light, undimmed, illuminates paths for continental creators, his legacy a living archive of Africa’s melodic might.

Rhythm Routes: Ebo’s Impact on Culture and Tourism

Ebo’s grooves mapped Africa’s cultural corridors, drawing pilgrims to Ghana’s shores. Highlife hotspots, Cape Coast’s palm wine bars, Accra’s night markets, thrummed with his influence, tourists tracing his steps from Saltpond homes to festival stages. International tours in his 70s and 80s, Spain’s festivals, the UK’s WOMAD, positioned Ghana as the heart of highlife, boosting ecotourism through music-led journeys. Collaborations with Jazz Is Dead bridged Los Angeles studios to Accra alleys, inviting global visitors to experience live sessions that blend heritage sites with sonic explorations.

His festival, launched pre-passing, envisioned annual gatherings celebrating highlife’s draw, workshops on guitar techniques, and dances fusing Fante steps with funk. This cultural tourism ripple: hotels humming with aficionados, local economies enlivened by rhythm seekers. Ebo’s story, from colonial echoes to global samples, narrates Africa’s allure, inviting wanderers to Saltpond’s beaches, where his spirit lingers in sea breezes and street strums.

Melodic Bonds: Unity Through Ebo’s Cultural Symphony

Ebo’s oeuvre orchestrated Africa’s unity; highlife was a harmony of diverse voices. Blending Ga, Ewe, Dagomba, and Akan traditions with Malian motifs, he wove pan-African threads, tracks like “Come Along” uniting coastal chants with inland beats. Collaborations transcended national borders: Fela’s Afrobeat exchanges and Pat Thomas’s shared stages fostered West African solidarity. In divided times, Ghana’s coups, regional conflicts, his music mended, communal dances defying discord.

Posthumously, tributes affirm this: Black Sherif’s ripples, global remixes sustaining bonds. For youth, Ebo’s message is: know your roots, innovate boldly, and dance the unity in diversity. His eternal groove, from Cape Coast to continents, binds Africa’s children in rhythmic embrace.