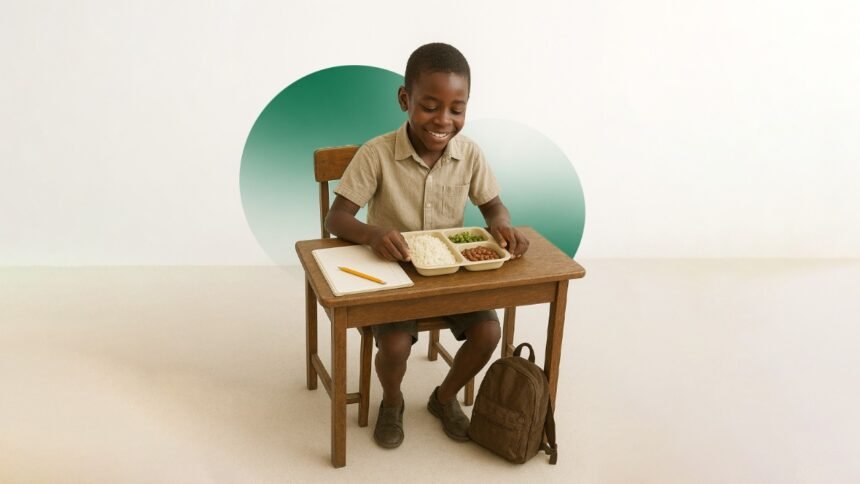

In a continent where millions of children still attend school on empty stomachs, the expansion of school feeding programs across Sub-Saharan Africa is being hailed as one of the most impactful social interventions of the decade. More than 65 million children in 44 African countries now benefit from daily school meals, according to the latest figures from the World Food Programme (WFP). This figure represents a sharp increase from pre-pandemic levels, when fewer than 50 million children were covered.

School feeding programs are not new, but their scale and urgency have taken on renewed importance. Across Africa, food insecurity has been worsened by climate shocks, conflict, and inflation, leaving families unable to guarantee even one full meal a day. By providing children with free, reliable meals at school, governments and aid agencies are not only fighting hunger but also keeping students in classrooms and improving their chances of learning.

For many children, the promise of a daily meal is the single most important reason they attend school. Teachers in rural Kenya, Malawi, and Niger have reported a noticeable drop in absenteeism since school meals were introduced. In some regions, enrolment has risen by as much as 20% within a single academic year. The message is clear: when hunger is taken off the table, children are free to focus on learning.

The benefits extend beyond nutrition and education. School feeding programs have a multiplier effect on local economies. In Ghana and Nigeria, for instance, governments source food locally, creating a guaranteed market for smallholder farmers. This approach not only sustains rural livelihoods but also shortens supply chains, reducing costs and ensuring fresher meals for children. It’s a model that development experts say could play a key role in strengthening food systems across Africa.

Yet challenges remain. Funding gaps threaten the continuity of many programs. The WFP estimates that an additional $5 billion annually would be needed to provide every child in Africa with school meals. Inflation and currency crises have pushed up the cost of food staples, making it harder for governments to sustain their programs without external support. In some countries, meal quality suffers as budgets are stretched thin, with schools providing only basic maize porridge or rice rather than balanced meals.

Despite these hurdles, the momentum is unmistakable. Countries like Ethiopia, Côte d’Ivoire, and Rwanda have announced plans to expand coverage to every public primary school within the next five years. Some are experimenting with digital tools, using mobile apps to track meal deliveries and prevent leakages in the supply chain. These innovations are designed to reassure both donors and taxpayers that resources are reaching the children who need them most.

Perhaps the most powerful argument for school feeding programs is their role in safeguarding the future of Africa’s children. Malnutrition during school years can lead to stunting, impaired cognitive development, and lower lifetime earnings. Studies have shown that every dollar invested in school feeding generates as much as $9 in economic returns through improved health, education, and productivity outcomes. In other words, school meals are not charity — they are a long-term investment in human capital.

On a more human level, the programs restore dignity and hope to children who might otherwise be trapped in cycles of poverty. In a village in northern Zambia, a headteacher recently described the visible transformation of her students after the introduction of school meals. “They arrive with energy, they stay awake during lessons, they smile more,” she said. “It is as if we have given them back their childhood.”

The expansion of school feeding in Africa is one of the continent’s most quietly significant revolutions. It is proof that even in times of economic hardship, targeted social programs can deliver tangible, life-changing results. The next challenge will be to ensure that these programs are not seen as temporary stopgaps but as integral parts of national education and health strategies. If governments, donors, and communities can keep the momentum going, they may not just be filling stomachs — they may be shaping a generation better equipped to break free from hunger and poverty.