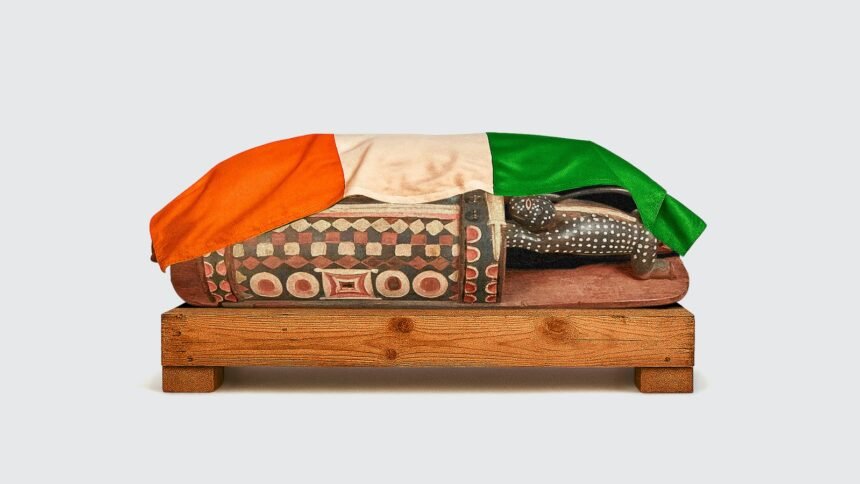

After more than a century, the long journey of the Djidji Ayôkwê—also known as the “talking drum”—from colonial trophy to national treasure is finally nearing its climactic finale. In a landmark move on July 7, 2025, the French National Assembly voted unanimously to return the revered drum to Côte d’Ivoire, following the Senate’s earlier approval, drawing to a close a saga that has stretched across generations.

This isn’t just another museum handover; it’s a symbolic reckoning. Originally seized from the Ébrié people by French colonial troops in 1916 during an effort to suppress resistance and control local communities, the drum weighs an imposing 430 kg (about 950 lbs) and spans nearly three metres in length. It functioned as a powerful communication tool—capable of sending warnings over vast distances, mobilizing villagers for ceremonies, and even acting as a pulse of cultural cohesion among the Atchan communities.

For years, the drum languished in the vaulted halls of the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris, restored in 2022 but effectively exiled from the land it once sounded across. That began to change when Côte d’Ivoire officially requested its return in 2018, part of broader efforts to reclaim a staggering 148 items taken during the colonial era. In 2021, President Emmanuel Macron publicly acknowledged France’s responsibility to restitute such items, offering hope that the long-held promises would finally materialize.

Yet getting the drum back proved anything but simple. Under France’s inviolable law for public collections, historic artefacts cannot be deaccessioned without new parliamentary legislation. So, the 2024 deposit agreement—which allowed for temporary hosting in Abidjan—acted as a stop-gap while lawmakers grappled with what to do next.

That patchwork approach—deposit now, permanent return later—typified France’s slow-moving restitution policy, criticized by African nations and international advocates alike. To date, only 27 items have been permanently returned, overwhelmingly small-scale or symbolic. The Sarr-Savoy report on African heritage restitution, published earlier this year, warns that such piecemeal progress risks reinforcing notions of symbolic rather than substantive reform.

But this July vote marks a genuine turning point. The 430 kg drum has finally received legal clearance to leave French national collections forever. The law cleared both houses unanimously, a rare moment of political alignment in France’s often-divided restitution debate.

In Abidjan, officials celebrated the drum’s imminent return. Maurice Kouakou Bandaman, Ivorian ambassador to France, described the legislation as “lawmakers recognising the full value of this artefact, the wrong that was done to Côte d’Ivoire, to the Bidjan people, to the Tchaman (Ébrié) people, through this theft.” UNESCO, which backed the initial deposit in 2024, also welcomed the move, citing deeper collaboration in line with its 1970 cultural property convention.

This isn’t simply about an ancient drum—it’s a test case for France’s evolving approach to colonial-era restitution. Will this wave open the floodgates, or fade into a trickle? Critics point out that the process has been painfully slow. While Benin, Senegal, and now Côte d’Ivoire have recovered some treasures, voices across Africa argue that far more remains unaddressed—and that true justice requires scale and speed.

France’s inalienability rules remain a major hurdle. Any future restitution requires new legislation. And while deposit agreements work in the interim, as with the drum, they don’t amount to ownership transfers. The Sarr-Savoy report emphasized that legal frameworks alone can’t resolve moral and historical claims. It advocated for more pragmatic, ethical museum practices—co-curation, digitization, shared exhibitions, and transparent lending—beyond legislative fixes.

There’s also geopolitical frisson. Much of the drum’s return and the broader restitution push are entwined with Macron’s ambition to reset France’s relationship with Africa—walking a tightrope between diplomacy and apology. The 2025 Africa-France summit spotlighted heritage restitution as a priority, extending the “new relationship” Macron first pitched in 2017.

Meanwhile, other European nations are playing catch-up. The Netherlands has returned hundreds of Benin bronzes, and Germany followed suit. The U.K., Spain, and others face growing calls to match the momentum. Observers watch closely: because if France, with its deeply entrenched legal conservatism, can take this step, it may set a powerful precedent.

That said, tangible restitution is still forthcoming. A date for the drum’s physical transfer hasn’t been set. French and Ivorian cultural teams are coordinating logistics for safe transport and installation. Officials in Abidjan anticipate a ceremonial welcome and permanent exhibition at the Musée des Civilisations de Côte d’Ivoire. But, as one insider observed, “the drum’s drums are still being tuned; once it finally beats again in its homeland, the resonance may be profound.”

In many ways, the drum’s return marks not an endpoint, but a starting signal. As African nations reclaim their stolen heritage, the question transforms: will restitution be occasional courtesy, or the foundation of a new, honest cultural partnership? For the Ébrié people and their drum, long silenced under colonial rule, the countdown to home has finally begun.