In the forests of Zamfara State, northwest Nigeria, a sinister economy has long been thriving in silence. Banditry—now seamlessly fused with terrorism—has become a profitable trade. But in one of the most horrifying incidents this year, it turned crueler than usual. Despite ransom payments, dozens of villagers were executed by their captors. It’s the kind of story that’s so common in the region it’s barely a blip on the global radar—but this time, the scale of horror demands attention.

According to local reports, 56 villagers were abducted by armed men believed to be part of a notorious gang operating across Zamfara and Katsina. Relatives of the victims say they were in touch with the kidnappers, negotiated tirelessly, and even paid the demanded ransoms. Then came the unthinkable: only 18 hostages were released. The rest—men, women, and possibly children—were slaughtered in cold blood. Their bodies were dumped at the edge of the forest like garbage.

For anyone following the security crisis in northern Nigeria, this is a brutal escalation of an already gruesome trend. Kidnapping for ransom has become institutionalized in rural states like Zamfara, Sokoto, Niger, and Kaduna. Villages are raided, communities taxed by force, and schools turned into hunting grounds for child abductions. Sometimes the kidnappers demand cattle. Sometimes cash. Sometimes fuel and food. What they always seem to get, however, is impunity.

The state government has condemned the killings but offered little in the way of a solution. Zamfara Governor Dauda Lawal called it “a heinous act of cowardice” and promised action, but locals have heard those words before. A week ago, it was a school in Kaduna. Two weeks before that, it was a farming village in Niger State. The Nigerian federal government continues to pledge tougher security measures, but the military is stretched thin, and confidence in local police is dangerously low.

Security analysts point to several overlapping crises. First, the collapse of local governance. Rural Nigeria is a place where state institutions don’t just perform poorly—they often don’t exist. Police stations are understaffed, roads are unpaved, and the law is mostly absent. In its place, criminal gangs and militias impose a violent, arbitrary form of order.

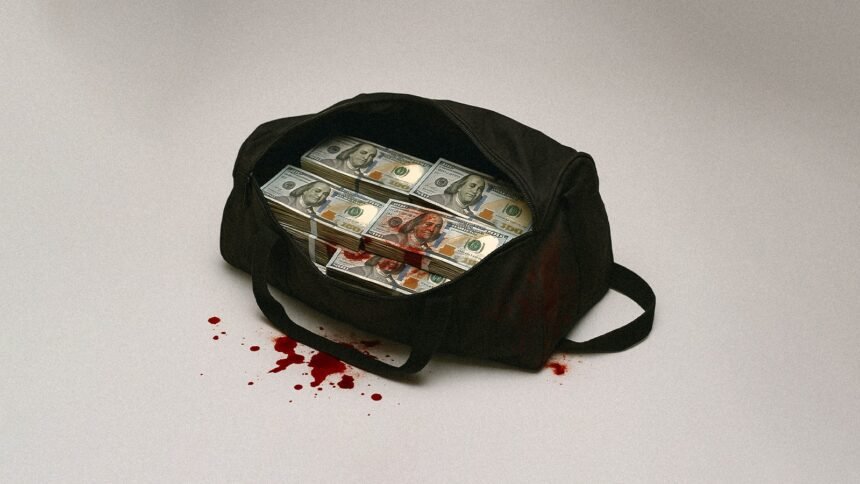

Second, the sheer profitability of kidnapping. A single ransom can fetch millions of naira (tens of thousands of US dollars), especially if the abducted individuals are from wealthy or politically connected families. What began as cattle rustling years ago has evolved into a streamlined extortion racket, complete with negotiators, informants, and brutal enforcers.

Finally, the larger climate of insecurity across West Africa fuels and fertilizes this crisis. Jihadist groups like Boko Haram and ISWAP are active further northeast, while armed herder–farmer conflicts rage in the Middle Belt. The line between ideologically driven insurgency and profit-driven violence is becoming increasingly blurry.

What makes the Zamfara massacre especially devastating is the sense of futility it leaves behind. For many rural Nigerians, kidnapping has become part of life. Families now keep emergency cash aside not for groceries or school fees, but in case a loved one is taken. Children are pulled from school. Women fear going to markets. Farmers abandon their fields.

The federal government, under President Bola Tinubu, has faced mounting pressure to act decisively. But critics argue that Abuja remains too focused on macroeconomic reforms and big-ticket infrastructure while security deteriorates in the rural heartlands. Some even suspect that high-level collusion helps keep the bandit economy alive.

This latest tragedy should be a turning point, but the country has seen too many turning points already. For the victims’ families, justice is a fading concept. Many will never even retrieve the bodies. Burials are hurried. Grief is swallowed. Life must go on, because in Zamfara and beyond, survival is resistance.

What’s clear now is that Nigeria’s kidnap crisis is no longer just about money. It’s about power, broken trust, and a state failing its most vulnerable. And when ransom becomes a death sentence, the old rules no longer apply.