Pan-African Reckoning: When Sovereignty Demands the Return of the Guilty

Across the continent, a quiet but insistent chorus has risen: African nations must no longer tolerate the spectacle of their most powerful citizens committing grave crimes at home, fleeing abroad, and then pleading for lenient repatriation when finally brought to justice. The case of Ike Ekweremadu — former Deputy President of the Nigerian Senate, convicted in London in 2023 of orchestrating an organ-trafficking conspiracy — has become the defining symbol of this struggle. Nigeria’s formal request in November 2025 for his transfer to serve the remainder of his sentence at home was swiftly rejected by British authorities, reigniting debates about sovereignty, impunity, and the right of African societies to confront their own transgressors on their own soil.

This is not about shielding the guilty. It is about insisting that justice for crimes conceived and rooted in Africa must ultimately be rendered in Africa — in courts that understand the cultural devastation of exploiting the poor, in prisons visible to the victims, and under laws that reflect the continent’s collective moral framework.

Nigerian Power’s Dark Underbelly: From Senate Chambers to Organ Bazaar

Ike Ekweremadu was no peripheral figure. For over a decade, he was one of Nigeria’s most influential politicians: Deputy Senate President, chairman of ECOWAS Parliament, and a kingmaker in Enugu politics. Yet beneath the tailored suits and diplomatic passports lay a chilling scheme. In 2022, Ekweremadu, his wife Beatrice, their daughter Sonia, and doctor Obinna Obeta lured a 21-year-old Lagos street trader to London with promises of work and a better life. The plan was simple and monstrous: harvest the young man’s kidney for Sonia, who suffered from kidney disease, paying him a mere £7,000 while arranging a £80,000 private transplant.

When the victim realised he was to be surgically violated, he fled the hospital and alerted police. The ensuing Old Bailey trial — the first prosecution under the UK’s Modern Slavery Act for organ trafficking — laid bare the mechanics of elite predation: forged documents claiming the donor was a cousin, bribes to medical staff, and callous disregard for the young man’s terror. Ekweremadu was sentenced to nine years and eight months, his wife to four and a half years, and Obeta to ten years.

The case sits alongside a grim roll-call of Nigerian elite criminality abroad: former Delta State Governor James Ibori jailed in London for laundering £250 million; ex-Bayelsa Governor Diepreye Alamieyeseigha convicted of money laundering before a controversial pardon; and countless lesser-known politicians who siphon billions, buy Mayfair mansions, and then cry foul when foreign courts intervene.

Diplomatic Impasse: UK-Nigeria Tensions Over Prisoner Transfer

In November 2025, Nigeria’s Foreign Minister Yusuf Tuggar led a high-level delegation to London to request Ekweremadu’s transfer under the UK-Nigeria prisoner exchange agreement. The British response was unequivocal: no. Officials cited the gravity of the offence, the need to complete rehabilitation programmes, and — crucially — lack of confidence that Nigeria would enforce the whole sentence.

The rejection exposed the hollowness of Nigeria’s selective outrage. While Abuja demanded Ekweremadu’s return as a matter of national dignity, more than 230 ordinary Nigerians languish in British prisons, many for minor drug offences, with little diplomatic effort made on their behalf. The Ekweremadu family’s campaign — complete with appeals to “African values” and claims of cultural misunderstanding — rang hollow against the victim’s testimony of terror and betrayal.

Commerce in Flesh: Organ Trafficking as Elite Exploitation

Organ trafficking is not an abstract crime; it is the commodification of African bodies by African elites. In Nigeria, poverty and desperation create a ready supply of potential “donors,” while weak regulation and corrupt medical networks facilitate extraction. Ekweremadu’s plot was not an anomaly — clinics in Lagos and Port Harcourt have been implicated in similar schemes, often targeting rural youths with promises of £2,000–£5,000 for a kidney that will fetch £100,000–£200,000 on the international market.

The victims are almost always the continent’s most marginalised: street traders, unemployed graduates, village farmers. The buyers are wealthy Africans or Middle Eastern clients who bypass years-long transplant waiting lists by purchasing human spare parts. The brokers — doctors, politicians, and intermediaries — operate with near impunity within Africa, facing consequences only when they attempt to complete the transaction abroad.

Ekweremadu’s conviction shone a rare spotlight on this trade, but it also revealed its asymmetry: the masterminds are tried in London. At the same time, the systemic conditions that produce victims remain unaddressed in Abuja.

Homeward Justice: The Case for African Courts and African Prisons

The deepest wound is not that Ekweremadu was jailed — it is that Nigeria lacked the institutions to prosecute him in the first place. Had the conspiracy been uncovered domestically, weak anti-trafficking laws, political interference, and a judiciary often beholden to the powerful would likely have ensured impunity.

Yet the solution is not to accept perpetual foreign oversight. African states must build the capacity to investigate, prosecute, and punish their own elites. South Africa’s post-apartheid truth commissions, Kenya’s recent anti-corruption courts, and Ghana’s Office of the Special Prosecutor offer models: independent institutions with public legitimacy, protected budgets, and the political will to jail the untouchable.

Prisoner transfer agreements should be reciprocal and conditional: Britain and other nations should return convicted African elites only when the receiving country demonstrates transparent sentencing enforcement, victim compensation funds, and public reporting. Until then, the refusal to repatriate serves as a painful but necessary incentive for reform.

Scales Rebalanced: Toward Genuine Continental Accountability

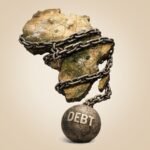

The Ekweremadu saga is a mirror held up to African governance. Every year, billions vanish into offshore accounts, bodies are bought and sold, natural resources are looted — and too often the perpetrators watch from London penthouses or Dubai villas while ordinary citizens bear the cost.

True Pan-African sovereignty is not achieved by demanding the return of the guilty to luxurious house arrest. It is achieved when Lagos, Nairobi, Accra, and Pretoria can say with credibility: “Bring them home — our courts are ready, our prisons are secure, and our people will finally see justice served.”

Until that day, the rejection of prisoner transfers — painful as it is — remains the continent’s most honest verdict on itself.