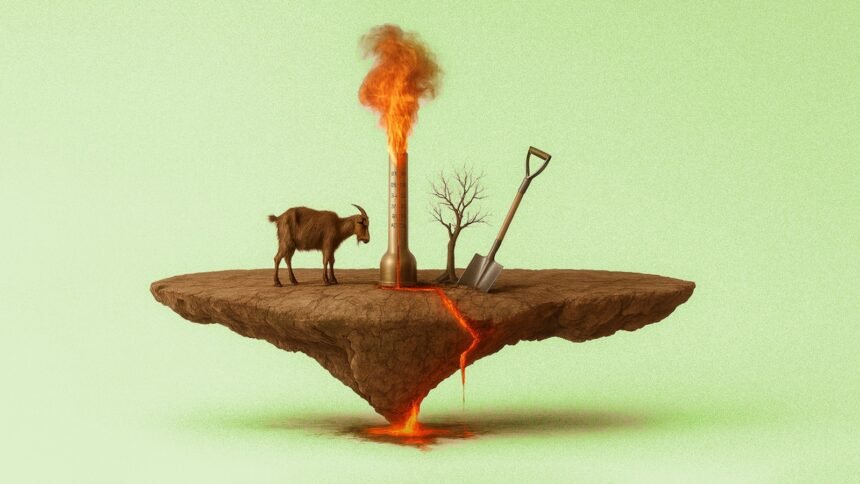

Eternal Sun, New Fury: Re-Defining Extreme Heat in the Rift

Extreme heat in East Africa is no longer the familiar dry-season furnace of ancestral memory. It is now a compound phenomenon: maximum temperatures routinely exceeding 42–46 °C, minimum temperatures refusing to drop below 28–30 °C, and wet-bulb readings creeping toward the human survivability ceiling of 35 °C for hours at a time. Unlike the oven-dry heat of the Sahel or North Africa, East Africa’s thermal extremes are often humid, driven by a warming Indian Ocean that pumps moisture-laden air over the highlands and rift valleys. This creates a slow-cooker effect: bodies cannot cool, livestock pant without relief, soils lose moisture through relentless evapotranspiration, and night offers no reprieve. What was once a seasonal trial has morphed into multi-month sieges, with heatwaves lasting 15–40 consecutive days, where they once endured barely a week.

The Escalating Curve: A Half a Century of Thermal Acceleration

Since reliable records began in the 1960s, East Africa has warmed 1.6–1.9 °C—roughly 50 % faster than the global land average and markedly faster than West Africa’s 1.3–1.5 °C. The shift is not gradual but stepped: a plateau until the late 1980s, then abrupt jumps coinciding with the 1997–98 El Niño, the 2015–16 event, and the ongoing 2023–2025 super-El Niño cycle. Heatwave frequency has increased fivefold, duration threefold, and intensity by 2–4 °C per event. Stations that never recorded 40 °C before 2000—Nairobi, Dodoma, Kisumu, Kampala—now do so almost every year. In the Horn, Lodwar (Kenya) and Berbera (Somaliland) have shattered 47 °C, while Juba and Mogadishu endure weeks above 44 °C with humidity that pushes wet-bulb readings above 32 °C for days. West Africa’s lethal humid heat peaks at higher absolute wet-bulb temperatures, but East Africa’s prolonged dry-heat episodes, layered on multi-year droughts, create a different, equally devastating signature.

Bodies on the Line: Scale and Distribution of Human Exposure

Approximately 260–280 million East Africans—over 55% of the sub-region’s population—now live in areas experiencing at least one prolonged heatwave annually. The most exposed belt stretches from the Afar Triangle through the Somali lowlands, across South Sudan’s floodplains, into northern and eastern Uganda, and down the east arc of Tanzania. Urban hotspots amplify risk: Greater Addis Ababa (33–36 °C nights), Dar es Salaam’s coastal furnace, and the refugee megacamps of Dadaab and Kakuma routinely exceed safe thermal thresholds for 100–150 days per year. Children under five (currently 62 million) and adults over 65 (projected to triple to 30 million by 2050) form the physiological front line. Outdoor workers—pastoralists, tea and coffee pickers, construction labourers, and the millions of women collecting water and firewood—lose 25–40 % of potential working hours when temperatures exceed 35 °C. Heat-related mortality is severely under-counted, but excess death modelling for 2020–2024 suggests 38,000–52,000 annual fatalities across East Africa, rivaling malaria in scale yet receiving a fraction of the attention.

The Drought-Heat Nexus: A Self-Reinforcing Spiral

East Africa’s droughts are no longer merely failures of rainfall; they are heat-amplified desiccation machines. Every additional degree of warming increases atmospheric moisture demand by roughly 7 %, sucking soils and vegetation dry even when rainfall is near normal. The 2020–2025 Horn of Africa drought—the most prolonged and most intense in the instrumental record—saw rainfall deficits of 60–80 % compounded by temperatures 3–5 °C above average, evaporating surface water before it could infiltrate. Vegetation cover collapsed, livestock mortality reached 60–80 % in pastoral zones, and 23–26 million people faced acute food insecurity by mid-2024. When rains finally returned in late 2024, they arrived as flash floods over baked, denuded soils, completing the whiplash cycle that now defines the region’s climate.

Ocean Ghosts and Jet Stream Whispers: Drivers Beyond CO₂

While cumulative CO₂ emissions explain the long-term trend, year-to-year escalation is turbocharged by Indian Ocean dipole extremes and an increasingly meandering subtropical jet stream. Successive positive dipole events (2019, 2021, 2023, 2024) have pumped record heat and moisture into the western Indian Ocean, creating marine heatwaves that persist for months and radiate warmth inland. Simultaneously, a warming Arctic has weakened the polar vortex, allowing mid-latitude Rossby waves to stall—locking high-pressure ridges over East Africa for weeks. These synoptic patterns, once rare, are now five to ten times more likely under current warming.

Adaptation on the Ground: From Indigenous Wisdom to High-Tech Hybrids

Communities are not waiting for global mitigation. Maasai and Borana pastoralists have revived traditional mobility corridors closed by colonial and post-colonial fencing. In Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Programme, heat-index-triggered cash transfers are now included. Kenya’s National Drought Management Authority issues livestock offtake subsidies when forecasts cross 38 °C thresholds. Agroforestry systems combining Grevillea robusta, mango, and drought-tolerant beans have raised farm incomes by 40–80% while lowering canopy temperatures by 4–6 °C. Solar-powered cooling hubs in refugee camps and urban markets—simple evaporative chambers and shaded misting zones—have reduced heatstroke admissions by half in pilot sites. Yet these successes remain scattered islands in a sea of unmet need.

The Finance Chasm: Billions Needed, Millions Delivered

East Africa requires an estimated $18–28 billion annually for heat-specific adaptation by 2030 (early warning systems, passive cooling in schools and health centres, heat-resilient seed systems, urban greening, and social protection indexed to temperature). Current flows—public and private combined—hover below $3 billion. The African Development Bank’s Africa Adaptation Acceleration Program and the loss-and-damage fund agreed at COP27 offer promise, but disbursement remains glacial. Innovative instruments—Kenya’s first heat-indexed insurance payout in 2024, Ethiopia’s forthcoming sovereign parametric heat policy—signal a path, but scaling demands orders-of-magnitude more capital and political will.

Tomorrow’s Thresholds: 1.5 °C vs Business-as-Usual

Under continued high emissions, East Africa crosses the threshold where wet-bulb temperatures of 35 °C become possible in coastal and lowland areas by the 2040s–2050s, rendering parts of the region seasonally uninhabitable without mechanical cooling. At 2 °C regional warming (likely by 2060 without drastic global cuts), the habitable window for outdoor labour shrinks to early morning and late evening year-round. Conversely, holding global warming to 1.5 °C limits the most catastrophic wet-bulb excursions and buys decades for orderly adaptation. The difference between these pathways is measured not in degrees but in hundreds of millions of livelihoods preserved or destroyed.

Dawn After the Furnace

East Africa stands at a hinge of history. The same solar abundance that once nurtured humanity’s first footsteps now threatens to cook the cradle. Yet the region that invented fire is re-learning how to live with it—blending ancestral resilience with twenty-first-century tools, demanding climate justice with an ever-louder voice, and proving that even in the hottest corner of a warming world, human ingenuity can still carve out corridors of greater hope. The question is no longer whether East Africa can adapt, but whether the rest of the world will finally pay the bill.