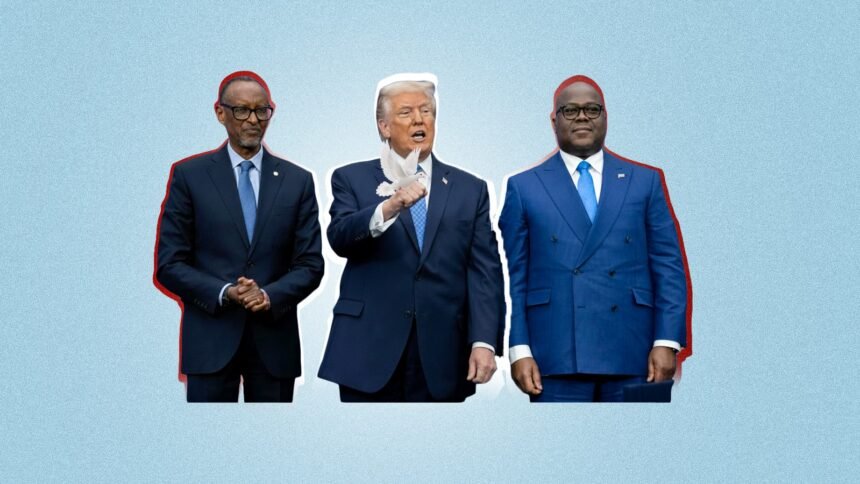

This week, U.S. President Donald Trump is set to host Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame and the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Félix Tshisekedi to sign the Washington Accords, an ambitious effort to address one of the continent’s most protracted crises.

For decades, eastern DR Congo has been a theatre of conflict involving dozens of armed groups, contested political narratives, and unresolved historical wounds. Now, after eight months of U.S.-brokered negotiations requested by Kinshasa, Washington believes it has brought the key actors together around a framework that could mark the start of a new chapter.

With DR Congo hosting some of the world’s most strategic minerals, including cobalt and coltan used in electric vehicle batteries, smartphones, and renewable energy systems, the stability of this region is closely tied to global energy and technology transitions. Washington’s decision to invest political capital in this process speaks to the significance of the stakes involved.

The agreement to be signed in the U.S. capital establishes a joint security coordination mechanism between Rwanda and DR Congo, along with a shared operational plan to neutralise the FDLR, a militia rooted in the remnants of those who orchestrated the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda and who have operated from eastern Congo for more than three decades. These fighters have been accused of targeting Tutsi communities in Congo and launching cross-border attacks on Rwanda, making them, from Kigali’s perspective, the single most persistent threat to regional peace.

The accords also outline a structured pathway for the safe return of refugees and create space for a future cycle of U.S.-driven investment in mining, energy, and infrastructure, linking stability with development in a way Washington has increasingly adopted across several mediation pathways.

Rwanda argues that the group’s continued existence, tolerated at various points by Congolese authorities, perpetuates insecurity and fuels cycles of displacement and ethnic violence. For Kigali, ending this threat is not a diplomatic preference but a national security necessity.

Despite numerous peace agreements signed over the years, from Lusaka to Pretoria to Addis Ababa, none have produced lasting results.

Eastern Congo remains host to over 100 armed groups, a reflection of unresolved internal political tensions, local governance failures, corruption, and the strategic value of the region’s mineral wealth. Armed factions regularly shift alliances, sometimes operating as extensions of political interests or economic networks.

Deep-seated discrimination against Kinyarwanda-speaking Congolese communities, combined with hate speech by certain elites, has repeatedly ignited violence. All this has kept the region vulnerable to flare-ups despite international efforts.

Analysts note that the absence of sustained external pressure, particularly on Kinshasa, has often allowed commitments to fade once the cameras move on.

President Paul Kagame recently said that past international interventions were too quick to issue statements and resolutions without addressing the fundamental drivers of instability.

He praised the U.S. approach for focusing on causes rather than symptoms, noting that rushed diplomatic visits in previous years were followed by announcements at the UN Security Council that seldom translated into action on the ground.

For Kigali, the Washington process marks a significant departure from these patterns.

Government spokesperson Yolande Makolo echoed this sentiment in interviews, describing the summit as the best chance in years for meaningful peace and emphasising that Congolese authorities themselves had asked Washington to step in.

If the agreement holds, the region could see reduced violence, fewer displacements, and renewed trust between the two countries whose relations have been strained for years. Stability could unlock major investment corridors, including U.S. and potentially Gulf-led infrastructure and mining partnerships.

Regional leaders from Kenya and Burundi will be present at the signing, underscoring the broad hope that progress in eastern Congo will have ripple effects across the Great Lakes, the Horn of Africa, and the wider continent.