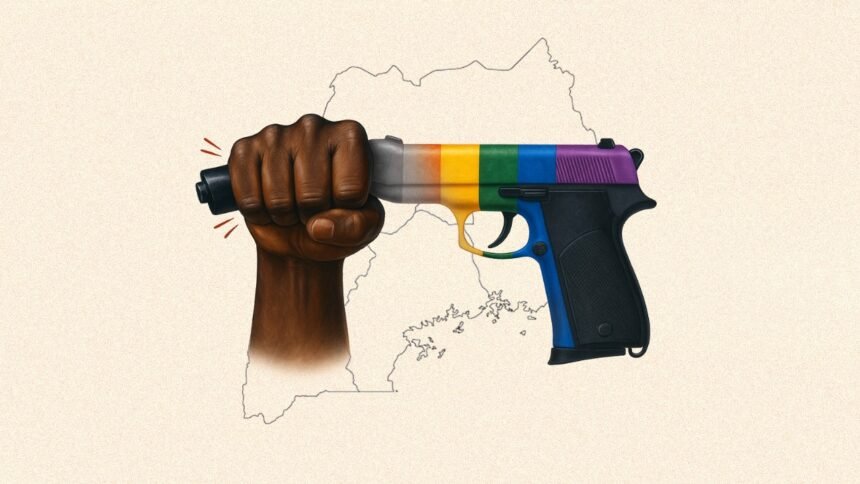

Uganda is once again hurtling toward the global spotlight, and not for reasons any nation would envy. A new proposal before Parliament seeks to criminalise not actions, not conduct, not behaviour, but simply being. Under the bill, merely identifying as LGBTQ+ could land someone in prison for up to ten years. In a world where governments debate budgets, trade, and development strategies, Uganda is debating identity—an intangible, unprovable part of the human spirit that lawmakers now want to police. The brazenness of it has startled even seasoned observers of African politics, many of whom assumed there were no new frontiers left in the continent’s long history of restrictive social legislation. It turns out there are.

The proposal has ignited debates that reach far beyond Kampala’s parliamentary corridors. Human-rights groups have called it a “criminalisation of existence,” a phrase that sounds dramatic until one reads the text of the bill. To “identify” as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, or queer becomes an offence, punishable by a decade behind bars. This is not about sexual acts, public advocacy, or even so-called “promotion” — the usual vocabulary of conservative legislation. The bill targets identity itself, a concept both private and fluid, and one that no state, however ambitious, can conclusively define or measure.

Yet the move makes political sense in a country where moral panics often serve as convenient distractions. Uganda has been grappling with inflation, youth unemployment, economic stagnation, and a government struggling to regain its shine. In such climates, some political actors reach instinctively for cultural battles, where enemies are easier to define than in the messy arena of macroeconomics. Casting LGBTQ+ Ugandans as a threat neatly redirects public exhaustion, offering a sense of restored control in a world that feels increasingly unwieldy.

In reality, Uganda’s LGBTQ+ community is neither secretive nor foreign. They are teachers, boda-boda riders, students, civil servants, farmers and church-goers. They are woven into the fabric of Ugandan society, even if that society often refuses to acknowledge them. But to lawmakers pushing the bill, the issue is not about coherence or practicality. It’s about symbolism. The legislation becomes a banner raised against “Western influence,” a defiant message that Uganda will chart its own moral course, regardless of international backlash.

And backlash there will be. Uganda has years of prior experience with punitive responses from Western governments and institutions over anti-LGBTQ+ laws. Aid freezes, travel restrictions and diplomatic isolation tend to follow these legislative battles. Yet supporters of the bill are unfazed. They argue that Western aid comes with strings they no longer wish to entertain. Others insist that the social conservative base is more valuable politically than any donor. The calculus is clear: in a world where foreign policy and domestic politics intersect, some Ugandan leaders have decided that aligning with cultural conservatism is worth the economic cost.

But the real cost will be paid by ordinary Ugandans. Criminalising identity creates immediate practical problems. Employers will fear hiring those who might one day be accused by disgruntled colleagues. Doctors and teachers could face moral dilemmas when treating or educating individuals who fall under suspicion. Landlords may evict tenants pre-emptively. Families might feel compelled to police relatives, not out of conviction but out of fear of being associated with a now-criminal category. The shadow of accusation becomes a weapon that can be wielded for personal or political revenge.

Meanwhile, law enforcement would be tasked with an impossible job: determining who identifies as what. Will suspicion itself become evidence? Will rumour be enough to justify arrest? Officers would be forced into roles that are neither legally clear nor ethically defensible. Uganda’s justice system, already stretched thin, may find itself inundated with cases rooted in little more than prejudice and conjecture.

The impact on young people could be especially devastating. Adolescents grappling with understanding themselves would be pushed into silence, fear and internal conflict. A generation already facing limited economic prospects would now navigate an additional layer of identity-based danger. The social consequences will be far-reaching, long-lasting, and mostly invisible, playing out in homes, schools, clinics and workplaces far from parliamentary debate chambers.

Yet amid the anxiety, there is also resistance. Ugandan activists—long accustomed to working in hostile conditions—are mobilising legal, social and diplomatic challenges. Civil-society groups are documenting abuses and preparing to challenge the bill in court if it passes. Some religious leaders have voiced concern, noting that criminalising identity contradicts principles of compassion. Even within Parliament, quiet dissent exists, though rarely spoken aloud.

Still, the bill represents a turning point. Whether or not it is enacted, Uganda has entered a new phase of legislating the personal. The world has seen countries criminalise speech, dress, and association, but few have attempted to criminalise identity itself. Uganda may be setting a precedent that other nations with similar populist impulses might be tempted to follow. That, more than anything, explains the alarm far beyond Africa’s borders.

The question now is whether Uganda will proceed down a path where identity becomes an offence, or whether public pressure—domestic and international—will halt the bill before it becomes law. In the meantime, millions watch a political drama where the stakes are nothing less than the right to exist without fear. It is a strange thing, in the twenty-first century, to witness a government debating whether certain citizens are allowed to be who they are. Stranger still is the fact that the debate may be decided by forces that have little to do with identity at all: political ambition, economic insecurity, and the timeless appeal of manufacturing an enemy.