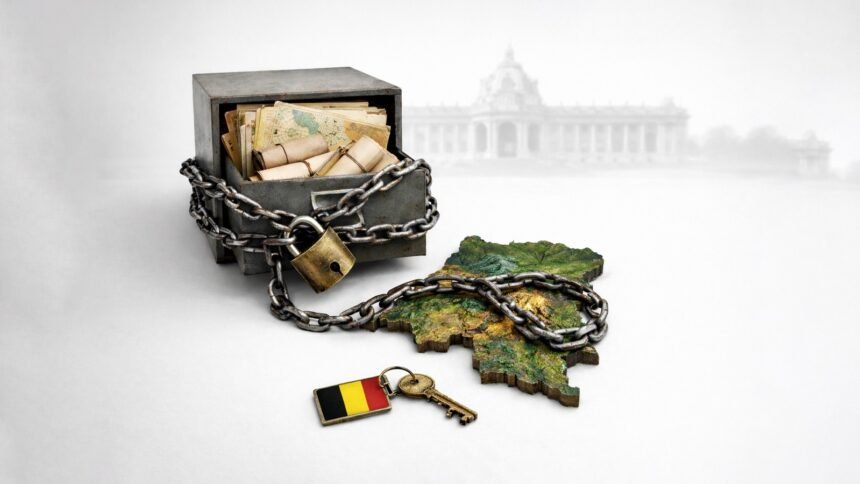

In the echoing halls of Tervuren’s Royal Museum for Central Africa, where gilded relics once glorified Belgium’s imperial grip, millions of records from the Democratic Republic of the Congo languish in archival limbo, a trove of geological maps, administrative ledgers, and resource surveys amassed during colonial plunder. This dispute, pitting Kinshasa’s sovereign demands against Brussels’ custodial claims, underscores a moral imperative: the DRC must gain unfettered access to these documents. Not merely for economic leverage in mapping its mineral wealth, but as a step toward rectifying historical injustices, empowering cultural sovereignty, and fostering Pan-African unity in the stewardship of shared heritage.

Pan African Imperative: Unity Through Repatriated Knowledge

The quest for access to colonial archives resonates as a Pan-African imperative, binding the continent’s museums in a collective pursuit of reclaimed knowledge. From Manchester’s Africa Hub crowdsourcing narratives on forty thousand artifacts to Libya’s Red Castle unveiling prehistoric mummies post-revolution, African institutions and their diaspora counterparts are dismantling imperial silos. In the DRC’s case, these records, spanning Leopold II’s brutal exploitation, hold the key to sustainable development, much like Ethiopia’s calls for the return of the Axumite obelisks or Nigeria’s Benin Bronzes campaign. Granting access would catalyze continental collaboration, enabling shared digital platforms where Senegalese scholars decode Saharan trade routes alongside Congolese geologists charting cobalt veins. This unity not only heals fragmentation but amplifies Africa’s voice in global heritage dialogues, transforming museums from colonial vaults into beacons of equitable knowledge exchange.

DRC Sovereignty: Reasserting Control Over Ancestral Data

At the heart of the Tervuren trove lies the DRC’s unyielding claim to sovereignty over data extracted during Belgium’s rapacious rule, which claimed millions of lives through forced labor and famine. These documents, including detailed geological surveys of copper-rich Katanga, were pilfered to fuel European industry, leaving the DRC, Africa’s largest copper producer, deprived of its own resource intelligence. Kinshasa’s partnership with KoBold Metals, a firm that pledges free public dissemination post-digitization, reflects a pragmatic bid for modernization, yet Belgium’s refusal to grant exclusive access suggests lingering paternalism. The DRC must prevail, not through private intermediaries alone, but via direct bilateral accords that affirm its right to these records as national patrimony. Such reclamation would enable local mining reforms, reduce dependence on foreign markets, and honor the resilience of Congolese communities, long denied the fruits of their soil.

DRC-Belgium Dialogue: Bridging Colonial Chasms

The DRC-Belgium dialogue over Tervuren’s archives offers a bridge across colonial chasms, demanding transparency to mend fractured ties. Belgium’s 2013 museum overhaul, rebranding it as a space for critical reflection, promised a break from glorifying empire, yet withholding records perpetuates asymmetry. Ongoing exchanges, as affirmed by Belgian officials, must evolve into concrete repatriation protocols, akin to France’s returns to Benin or Germany’s to Namibia. For the DRC, access means unlocking economic potential amid Western competition for critical minerals and countering China’s dominance in cobalt supply chains. This dialogue, if equitable, could model restorative justice, in which Belgium funds digitization while ceding control, thereby fostering mutual tourism ventures, such as joint exhibitions on shared histories. Ultimately, bridging these chasms affirms that true partnership arises from acknowledging past atrocities rather than perpetuating archival monopolies.

African Museums Renewal: Guardians of Continental Narratives

African museums are undergoing a profound renewal, emerging as guardians of narratives once silenced by colonial curators. Libya’s Red Castle, reopened in 2025 after Gaddafi’s fall, repatriated artifacts from the US and Europe, echoing Manchester’s invitation to diaspora communities for insights into Igbo heritage. In Egypt, the Grand Egyptian Museum’s inauguration spotlights pharaonic splendor, while Cairo’s craft districts preserve living traditions. The Tervuren case amplifies this renewal: granting DRC access would inspire similar actions across the continent, from South Africa’s Apartheid Museum digitizing resistance archives to Kenya’s national repositories reclaiming Maasai artifacts. These institutions, by prioritizing source communities, transform from elite enclaves into inclusive spaces in which renewal means not just preservation but active decolonization—ensuring that Africa’s stories are told by Africans, for Africans.

Colonization Records: Echoes of Exploitation Demanding Redress

Colonization records, like those in Tervuren, echo exploitation’s grim legacy, demanding redress through unrestricted access for the DRC. Amassed under Leopold’s personal fiefdom, these papers detail resource extractions that fueled Belgium’s wealth while devastating Congolese societies—maps charting mineral veins alongside logs of coerced labor. Belgium’s stance, classifying them as federal archives immune to private deals, ignores the moral debt; the DRC’s sovereign right supersedes such technicalities. Redress could manifest through phased digitization, with Congolese experts leading interpretations, mirroring global shifts such as the UK’s acknowledgment of Mau Mau records. These echoes, if heeded, would dismantle neocolonial barriers, empowering the DRC to harness its cobalt and copper for equitable growth, while educating future generations about the costs of imperialism.

Cultural Protection: Safeguarding Heritage from Lingering Shadows

Cultural protection in the shadow of colonialism necessitates safeguarding heritage through DRC-led access to Tervuren’s vaults. These records are not inert documents but cultural artifacts that encode indigenous knowledge, geological insights intertwined with oral histories of land stewardship. Belgium’s reluctance risks perpetuating erasure, much as unreturned artifacts in European museums stifle African self-determination. Protection requires collaborative frameworks: joint custodianship, in which the DRC directs use, preventing commercial monopolies while ensuring public benefit. This aligns with UNESCO principles, echoing the protections afforded to Libya’s Ghadames and Egypt’s Nubian sites. By safeguarding thus, the continent fortifies its cultural sovereignty, turning protection into a shield against exploitation and a catalyst for authentic representation.

Tourism Horizons: Unveiling Shared Pasts for Future Journeys

Tourism horizons brighten when colonial archives such as Tervuren’s are unveiled through access to the DRC, inviting journeys into shared pasts. Digitized records could spawn eco-tourism trails tracing mineral histories, complementing Egypt’s Red Sea marinas or Nigeria’s Detty December festivities. For the DRC, this means heritage routes in Katanga, drawing global visitors to sites of resilience, boosting economies strained by conflict. Belgium, by facilitating access, could co-create exhibitions fostering reconciliation tourism, akin to Rwanda’s genocide memorials. These horizons promise sustainable revenue, Egypt’s nineteen million visitors in 2025 attest to the draw of heritage, while educating travelers about Africa’s agency, transforming museums into portals for empathetic exploration and mutual enrichment.