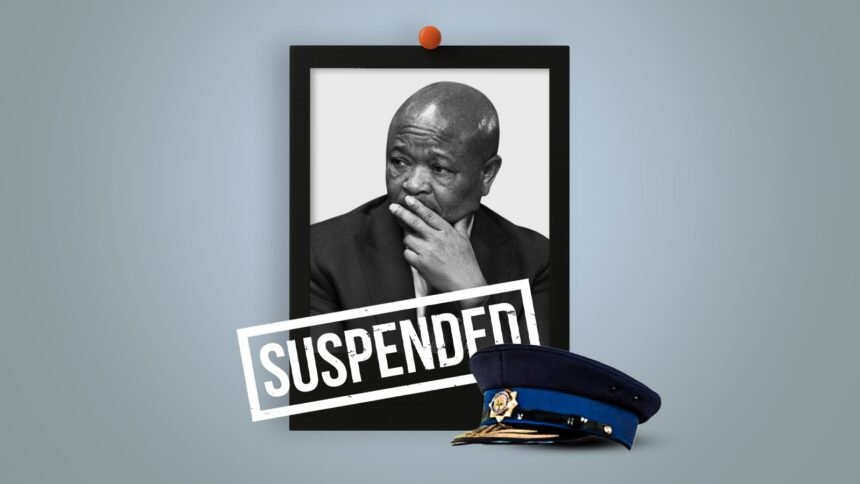

In a move as dramatic as any courtroom thriller, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa has suspended Police Minister Senzo Mchunu and ordered a sweeping judicial inquiry into allegations that read like a script for a crime noir film. With murmurs of collusion between the top brass of law enforcement and organized crime echoing through the corridors of Pretoria, the suspension signals a watershed moment for South Africa’s democracy and its ongoing struggle with corruption and accountability.

The allegations themselves are damning. According to internal documents leaked to multiple news outlets and whistleblower testimonies presented to Parliament’s oversight committees, Mchunu allegedly maintained close ties with figures implicated in a sprawling criminal syndicate responsible for illicit mining operations, extortion, and arms smuggling. These groups, widely believed to operate across provincial lines and with links to international crime networks, have for years operated with impunity in areas where law enforcement presence should have been strongest.

President Ramaphosa’s decision to suspend Mchunu did not come lightly. Sources close to the presidency indicated that pressure had been mounting from within the African National Congress (ANC), civil society groups, and even from international partners concerned about the increasingly porous boundary between South African law enforcement and the criminal underworld. The straw that broke the camel’s back, according to insiders, was an intercepted communication in which a senior crime boss mentioned a “green light from the top” believed to refer to the minister himself.

The response has been swift. A commission led by retired judge Thembile Masuku has been tasked with uncovering the extent of criminal infiltration within the police service. In an unusually strong statement, Masuku pledged that “no one, regardless of rank or connection, will be spared scrutiny.” Already, several high-ranking police officials have been placed on administrative leave pending the commission’s findings, and prosecutors are reportedly preparing a string of indictments.

The scandal has plunged South Africa into a national reckoning. Public trust in law enforcement, already shaken by years of corruption, police brutality, and ineffectiveness, is now approaching a breaking point. In communities long plagued by gang violence and criminal syndicates—such as those in the Eastern Cape and parts of Gauteng—residents voice a bitter sense of vindication. “We’ve been saying for years the police were in on it,” said one community activist in Soweto. “Now they can’t pretend anymore.”

But the implications stretch beyond mere scandal. The ANC, still struggling to rebrand itself after the Zuma years, finds itself once again battling the specter of state capture. Political analysts suggest that Ramaphosa, by acting decisively, is attempting to reassert the moral authority of his presidency. “This is a high-stakes move,” said Professor Thandi Mahlangu of the University of Johannesburg. “If the probe uncovers a deeply embedded criminal-political nexus, Ramaphosa will need to do more than suspend a minister—he’ll need to clean house across multiple departments.”

International observers are also paying close attention. South Africa, long hailed as a democratic beacon on the continent, now faces uncomfortable questions about the integrity of its institutions. Western governments, including the United States and members of the European Union, have reportedly contacted Pretoria seeking clarification on how far the rot goes. With South Africa hosting key diplomatic and commercial roles on the continent, its stability is not just a domestic issue but a regional concern.

Meanwhile, opposition parties are wasting no time capitalizing on the crisis. The Democratic Alliance has called for a no-confidence motion not just in Mchunu, but in the broader Cabinet, while the Economic Freedom Fighters are demanding a full audit of police finances and procurement processes over the past decade. In Parliament, the air is electric with accusations, finger-pointing, and barely concealed panic.

Back on the ground, ordinary South Africans are watching with weary skepticism. “We’ve seen ministers fall before,” said one resident of Durban, “but nothing ever really changes. We want arrests, not press conferences.”

Perhaps that is the ultimate test of this moment. If Ramaphosa’s response is viewed as a mere performance—another symbolic act to placate the media and the public—it could backfire disastrously. But if the commission leads to real reform, prosecutions, and a restructuring of law enforcement, it could mark a turning point for a nation sorely in need of institutional redemption.

For now, South Africa waits, watches, and wonders whether this is the beginning of a new chapter—or just another episode in a long saga of impunity.