When African leaders closed the 39th Ordinary Session of the African Union (AU) Assembly in Addis Ababa on 14 February 2026, they sent a clear message: Africa will not meet its development ambitions while hundreds of millions still lack clean water and basic sanitation.

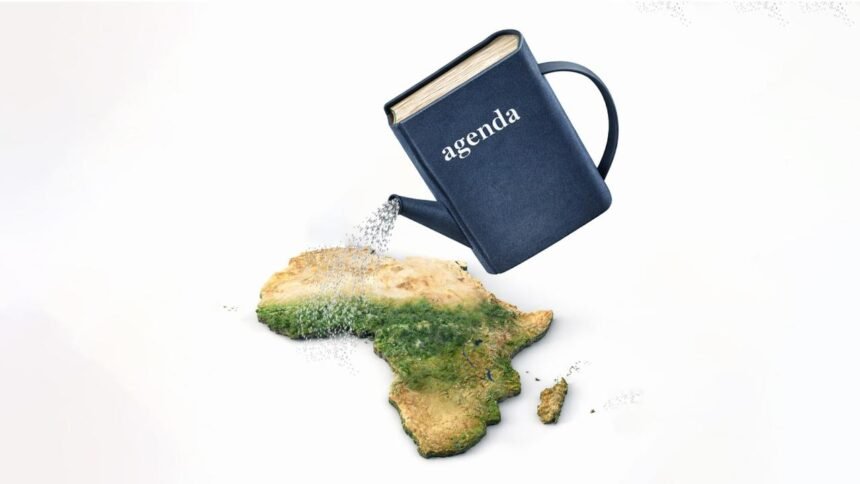

By declaring 2026 the year of Assuring Sustainable Water Availability and Safe Sanitation Systems to Achieve the Goals of Agenda 2063, the AU has put taps, toilets, and treatment plants at the centre of its long‑term vision for a prosperous, peaceful, and integrated continent.

Behind this theme lies a stark reality. An estimated 411 million Africans lack basic drinking water services, 779 million lack basic sanitation, and about 839 million lack access to basic hygiene.

These deficits are not only a violation of fundamental rights; they also drag down economic growth, fuel preventable disease, and deepen inequalities both between and within countries. As climate change drives more frequent droughts, floods, and water‑borne outbreaks, the human and economic costs of inaction are mounting across the continent.

The decision to spotlight water and sanitation in 2026 emerged from the Addis Ababa summit, where heads of state acknowledged that Africa is off track on water‑related Sustainable Development Goals and Agenda 2063 targets.

AU Commission ChairpersonMahmoud Ali Youssouf described water security as a strategic issue for development, peace, and climate, arguing that it underpins health systems, food production, energy supply, and social stability in every region.

Recent assessments support that view: more than half of African households report regular challenges accessing safe water, with rural communities and residents of informal urban settlements facing the most severe shortages.

Water‑related illnesses remain a leading cause of preventable death among children, and only around half of health facilities on the continent have basic water services, weakening emergency preparedness and routine care alike.

Commissioner Moses Vilakati, who oversees Agriculture, Rural Development, Blue Economy, and Sustainable Environment (ARBE), has pointed to a persistent gap between required and actual investment in water and sanitation, warning that inclusive growth and poverty eradication will remain out of reach if that financing gap is not closed.

For many governments, the 2026 theme is both an alarm bell and an opportunity: a chance to re‑order priorities, mobilise new resources and bring water and sanitation from the margins of policy to its centre.

By linking the 2026 theme directly to Agenda 2063, the AU’s 50‑year blueprint for an integrated, prosperous, and peaceful Africa, leaders are signalling that water and sanitation are cross‑cutting enablers rather than narrow-sectoral issues.

Reliable services shape almost every aspiration in the agenda, from healthy citizens and skilled youth to environmentally sustainable economies and resilient infrastructure capable of withstanding climate shocks.

The choice of theme also aligns with the Africa Water Vision 2063, a continental framework endorsed under the African Ministers’ Council on Water (AMCOW).

That vision calls for “a water‑secure and resilient Africa with safe sanitation for all,” backed by universal access to safely managed water, sanitation, and hygiene, as well as sustainable water availability for households, agriculture, industry, and ecosystems.

Africa Water Vision 2063 embeds the Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystems (WEFE) nexus, recognising that the same river or aquifer can power turbines, irrigate fields, sustain fisheries, and support fast‑growing cities when managed collaboratively and equitably.

This systems‑based approach is increasingly visible in AU messaging, which stresses that water policy must be coordinated with energy planning, agricultural strategies, and environmental protection, rather than handled in isolation by under‑resourced utilities.

To ensure that the 2026 theme delivers tangible results rather than remaining a slogan, the AU is developing an implementation strategy focused on governance, finance, partnerships, and technical capacity. One priority front is sustainable water availability.

Member states are being encouraged to expand storage, use groundwater more strategically, and build climate‑resilient infrastructure through integrated water resources management and WEFE‑based planning.

Restoration projects in Ethiopia’s highlands, where check dams, terraces, and tree planting have helped restore perennial streams and improve agricultural yields, are widely cited as examples of how better water management can transform local livelihoods and reduce climate vulnerability.

A second front is safe sanitation systems. With hundreds of millions still practising open defecation or relying on unsafe facilities, the AU is urging governments to prioritise rural communities and fast‑growing informal settlements around major cities.

Experience from East African urban areas shows that extending piped networks, upgrading on-site sanitation, and strengthening utility management can reduce disease, save households time and money, and make service providers more financially sustainable when tariffs and subsidies are carefully designed.

The third front is policy and governance. In many countries, water and sanitation services are constrained by weak monitoring systems, fragmented mandates, and unpredictable financing.

The AU is calling for higher public budget allocations, clearer regulatory frameworks, and better data, pointing to reforms in some North African states where long‑term planning and investment have led to near‑universal urban access and improved service quality. Stronger governance, AU officials argue, is essential both to attract private capital and to ensure that investments reach the communities most in need.

The fourth front is transboundary cooperation. Africa has more than 60 shared river basins and numerous transboundary aquifers, making collaboration essential to avoid conflict and maximise shared benefits.

Sensitive negotiations in basins such as the Nile, where large upstream hydropower projects and downstream water security are tightly linked, illustrate why the AU is prioritising joint planning, data sharing, and dispute‑resolution mechanisms as part of its 2026 agenda. The Union sees these cooperative frameworks as key not only to regional peace, but also to large‑scale, climate‑resilient infrastructure that no single country could finance or manage alone.

Within the AU architecture, the ARBE department is leading the rollout of the theme, working with member states, regional economic communities, civil society, and technical partners to integrate water and sanitation into national strategies.

Its broad portfolio, covering agriculture, rural development, environmental management, and the blue economy, enables it to connect water issues to food systems, coastal development, and climate adaptation across the continent. Specialised bodies established under AMCOW and related initiatives are supporting countries with research, policy advice, and capacity‑building, particularly in drought‑prone and semi‑arid regions.

International partners are expected to play a significant role in closing Africa’s investment gap. The United Nations Development Programme and other agencies estimate that roughly 30 billion dollars per year will be needed by 2030 to deliver universal, climate‑resilient water and sanitation services across the continent.

The AU is pressing for investments that empower local authorities and communities, especially women, youth, and marginalised groups, who are often at the forefront of innovative, low‑cost solutions in both rural and urban settings.

Ultimately, the success of the 2026 theme will be measured not in summit communiqués but in household taps that run, toilets that work, and rivers and aquifers that are protected rather than depleted. Governments are being urged to align with the theme in their budgets and development plans, explore blended public-private finance, and share effective practices through regional platforms so that local successes can be replicated and scaled.

For ordinary Africans, the stakes are immediate: a reliable water point can free a child to attend school instead of spending hours fetching water; a functioning toilet and handwashing station can protect a family from disease; a well‑managed watershed can shield a neighbourhood from floods and secure a farmer’s harvest.

The AU’s focus on water and sanitation in 2026 is framed as a call to action, but it is also a test of political will. If commitments made in Addis Ababa translate into pipelines, treatment plants, safe toilets, and restored ecosystems, the goal of a water‑secure and resilient Africa by 2063 will move from aspiration to credible, visible progress in the lives of millions.