Whispers of the Ancestral Winds: Contextualizing Climate Shifts Across the African Tapestry

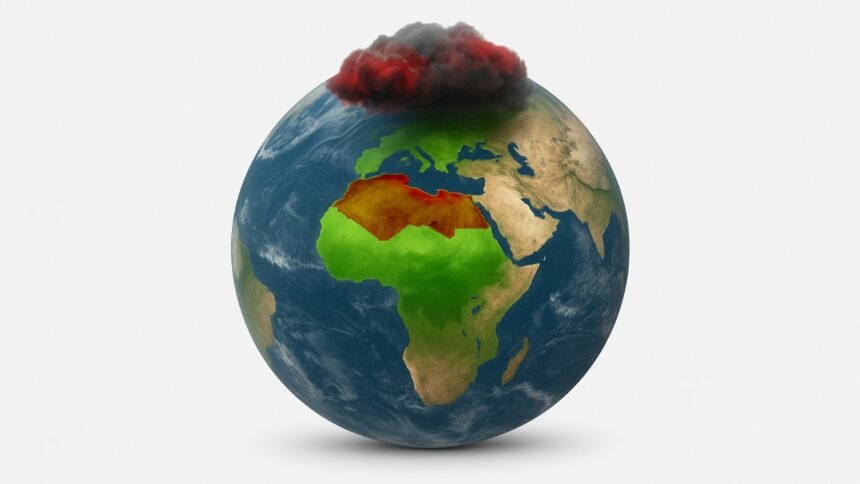

In the expansive and diverse landscape of Africa, where ancient civilizations have thrived amid shifting sands and fertile valleys, climate change presents itself as an immediate and profound challenge that resonates with the continent’s deep-rooted ethos of unity, endurance, and communal harmony. Pan-Africanism, embodying the shared heritage and collective aspirations of African peoples, serves as a guiding framework for understanding and addressing these environmental transformations, especially in North Africa. This region, spanning countries such as Egypt, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya, acts as a vital bridge between the arid expanses of the Sahara Desert and the temperate influences of the Mediterranean Sea, creating a unique mosaic of ecosystems that are both resilient and vulnerable.

Africa as a whole contributes only a small fraction—around two to three percent—of global greenhouse gas emissions. Yet, it endures some of the most severe repercussions of climate change due to its geographical diversity, socioeconomic structures, and historical underinvestment in infrastructure. In North Africa, this irony is starkly evident, as temperatures have risen at rates double the global average since the 1970s, with increases of 0.2 to 0.4 degrees Celsius per decade, particularly during summer months. The region’s arid and semi-arid climates, combined with high population densities in coastal zones, heighten exposure to risks such as sea-level rise, heat stress, and water scarcity. Coastal cities such as Alexandria in Egypt and Tunis in Tunisia, home to millions, are particularly susceptible to flooding and erosion, which threaten livelihoods dependent on agriculture, tourism, and fisheries.

The contextual foundation of climate adaptation in Africa draws heavily from indigenous knowledge systems that have sustained communities for millennia. Nomadic pastoralists in the Sahel and oasis farmers in the Maghreb have long employed techniques like rotational grazing and water conservation to cope with natural variability. Today, these traditions intersect with modern challenges posed by human-induced climate change, including rapid urbanization and geopolitical tensions over shared resources, such as the Nile River. Pan-African solidarity emphasizes the interconnectedness of the continent’s regions, recognizing that North Africa’s challenges—such as groundwater depletion and desertification—ripple southward, affecting food security and migration patterns across borders. Adaptation efforts must therefore integrate this holistic view, promoting strategies that respect cultural identities while leveraging technological advancements to build resilience. By viewing climate change through a Pan-African lens, North Africa can transform its vulnerabilities into opportunities for continent-wide collaboration, ensuring that adaptation is not just a response to crisis but a pathway to sustainable prosperity.

Echoes from the Sahara: Tracing the Historical Footprints of Climate Variability

The historical narrative of climate change in Africa is akin to an enduring epic, chronicling cycles of abundance and adversity that have molded societies over centuries. In North Africa, the Sahara’s vast dunes bear witness to these shifts, with documented temperature escalations and precipitation fluctuations dating back to the early twentieth century. Since the 1970s, mean annual temperatures have increased significantly, outpacing global trends. At the same time, precipitation patterns have shown a marked decline from 1971 to 2000, followed by partial recoveries in areas such as Algeria and Tunisia since 2000, and Morocco since 2008. These changes have compounded existing pressures from colonial histories, where resource extraction disrupted traditional land management, leaving legacies of vulnerability that persist today.

Key historical events underscore the region’s climatic volatility. The mid-1970s Sahel drought, which extended into North Africa, triggered widespread famine, displacement, and economic hardship, highlighting the fragility of rain-fed agriculture and pastoral systems. In Egypt, storm surges along the Nile Delta in 2010, 2011, and 2015 caused coastal flooding up to 1.2 meters above sea level, damaging infrastructure and lowlands. Similarly, urban droughts, akin to Cape Town’s 2015-2018 crisis in southern Africa, have parallels in North African cities where groundwater salinization and overexploitation have intensified since the mid-twentieth century. Temperature rises of 0.75 to 1.2 degrees Celsius since 1960 in central regions echo similar warming in the north, contributing to increased aridity and reduced snowfall in the Atlas Mountains, which affects meltwater recharge for irrigation.

These historical patterns are intertwined with socioeconomic developments, including post-independence pushes for industrialization that often overlooked environmental sustainability. Transboundary issues, such as disputes over the Nile Basin waters shared by Egypt and upstream nations, have historical roots in colonial treaties and continue to influence adaptation strategies. Pan-Africanist ideals call for reclaiming this history by revitalizing indigenous practices, like the ancient qanat irrigation systems in Morocco and Algeria, which have enabled communities to thrive in arid conditions for generations. By examining these footprints, North Africa can draw lessons from past adaptations—such as community-based resource sharing during dry spells—to inform contemporary policies, fostering a resilient future grounded in collective memory and innovation.

Tempest in the Maghreb: Unveiling the Multifaceted Climate Consequences

The ramifications of climate change in North Africa unfold like a relentless storm across the Maghreb, manifesting in a complex array of environmental, social, and economic disruptions that challenge the region’s very foundations. Projections indicate that summer temperatures could exceed 46 degrees Celsius by mid-century, with heatwaves occurring four to six times more frequently under a 1.5-degree Celsius warming scenario compared to previous generations, escalating to nine to ten times under higher emissions paths. This intensifying heat, combined with decreasing precipitation—particularly in northwestern areas at warming levels of 2 degrees Celsius and above—amplifies drought frequency and duration, potentially doubling from two to four months in affected zones.

Water scarcity stands as a central consequence, with over 80 percent of the population already grappling with stressed resources, exacerbated by groundwater depletion and salinization. In agriculture, the lifeblood of North African economies, shortened growing seasons and reduced yields threaten food security; for instance, olive production in Tunisia and Morocco could decline significantly at 1.5 degrees Celsius, while overall agricultural productivity in rain-fed systems might halve. Desertification advances inexorably, eroding fertile lands in Algeria’s high plateaus and Morocco’s coastal plains, leading to biodiversity losses where up to 20 percent of mammals may lose suitable habitats above 2 degrees Celsius warming.

Health impacts are profound, with surges in heat-related illnesses, respiratory issues from dust storms, and vector-borne diseases like malaria expanding their range. Coastal vulnerabilities are acute, as sea-level rise inundates deltas and erodes shorelines, potentially displacing millions in cities like Alexandria, where damages could reach tens to hundreds of billions of dollars by 2050. Economically, these effects have already reduced GDP per capita by around 13.6 percent from 1991 to 2010, with sectors like tourism, manufacturing, and infrastructure bearing heavy losses. Socially, the consequences fuel migration and potential conflicts over transboundary resources, such as shared aquifers and rivers, while gender-differentiated vulnerabilities—often under-researched in the region—place additional burdens on women in rural areas.

Yet, within this tempest, Pan-African unity provides a beacon, encouraging shared strategies that view these consequences not as isolated threats but as interconnected challenges demanding collaborative action. By addressing them holistically, North Africa can mitigate cascading risks, from livelihood diminishment to rising inequalities, turning adversity into a forge for stronger, more equitable societies.

Greening the Nile’s Legacy: Harnessing Financial Flows for Climate Fortitude

Green finance serves as a crucial lifeline in bolstering Africa’s climate adaptation endeavors, directing capital toward sustainable infrastructures and practices that echo the continent’s rich legacy of resource stewardship, much like the ancient Nile’s role in nurturing civilizations. In North Africa, where adaptation requirements are projected to cost hundreds of billions by mid-century, these financial mechanisms are indispensable for closing the gap between urgent needs and available resources. Currently, adaptation finance accounts for approximately one-third of the continent’s climate funding, with annual flows of around $ 30 billion. However, this falls short of the estimated 200 billion needed yearly by 2030, and even more—up to 2.8 trillion annually—for broader climate resilience.

Progress in green finance is evident through initiatives such as green bonds and sustainable banking, with countries like Morocco, Egypt, and Tunisia establishing regulatory frameworks for green bond issuance and national climate funds. Morocco has pioneered sovereign green bonds to fund solar and wind projects, while Egypt leverages corporate green bonds for renewable energy and infrastructure. These efforts mobilize private investments for solar-powered irrigation in Egypt and reforestation in Tunisia, promoting low-carbon transitions in agriculture and energy. Blended finance models, which combine public grants with private capital, are gaining traction, alongside technological innovations such as mobile banking for climate-smart loans in rural areas, thereby enhancing access for smallholder farmers.

Despite advancements, challenges abound, including high perceived investment risks due to economic instability, limited access for small and medium enterprises, and underdeveloped markets that hinder green bond growth. Regulatory inconsistencies and data transparency issues further deter investors, while dependence on foreign capital exposes projects to global volatility. In North Africa, these hurdles are compounded by water-intensive projects that conflict with local needs; however, prospects are emerging through the expansion of public-private partnerships and international collaborations with bodies like the Green Climate Fund.

Pan-African principles infuse green finance with equity, ensuring funds reach marginalized communities and support inclusive growth. By harnessing these flows, North Africa can revitalize its oases, strengthen its food systems, and reduce its reliance on fossil fuels, paving the way for a resilient and sustainable legacy.

Trials of the Desert Nomads: Navigating Adaptation Hurdles with African Solidarity

Adapting to climate change in North Africa resembles the arduous journeys of desert nomads, fraught with obstacles that demand ingenuity, perseverance, and collective support to overcome. Governance deficits, often stemming from colonial-era structures, impede effective policy execution, with a disproportionate emphasis on mitigation over adaptation despite rising disasters like Libya’s devastating floods. Institutional barriers include fragmented approaches, slow policy implementation, and inadequate coordination between national and local levels, complicating responses to water shortages and food insecurity.

Socioeconomic vulnerabilities—poverty, inequality, youth unemployment, and gender disparities—amplify risks, limiting communities’ ability to adopt resilient technologies. In rural areas, small-scale farmers face high costs for sustainable practices like drought-tolerant crops, while women bear disproportionate burdens due to limited access to resources and decision-making. Transboundary challenges add layers of complexity, with shared water bodies, such as the Nile, and aquifers sparking tensions amid dwindling supplies, which are exacerbated by political instability in countries like Libya.

Financial shortfalls are acute, with adaptation finance disbursements low—only 15 percent in North Africa compared to global averages—due to bureaucratic hurdles and capacity issues in accessing funds from mechanisms like the Adaptation Fund. Data gaps, limited research funding (with African institutions receiving just 14.5 percent of climate-related funds), and low awareness of climate services (23 to 66 percent across the continent) further hinder progress. Technological and infrastructural barriers, such as poor weather data availability and overcentralization, undermine adaptive capacity.

Nevertheless, these trials are surmountable through Pan-African solidarity, which promotes knowledge exchange through regional bodies for ecosystem restoration and the development of early warning systems. Indigenous methods, like community-managed water harvesting, offer cost-effective solutions, while empowering women and youth infuses fresh innovation. Overcoming these hurdles requires a unified African approach, converting challenges into avenues for inclusive development and environmental guardianship.

Horizons of the Rising Sun: Envisioning Future Trajectories in Climate Adaptation

Peering into the future of climate adaptation in Africa, with North Africa leading the charge, reveals a landscape of potential innovation set against a backdrop of escalating uncertainties, much like the promise of dawn over the horizon. Projections warn of heightened extremes—droughts, floods, and heatwaves intensifying under warming scenarios, with meteorological droughts potentially doubling in duration and urban flooding exposures rising dramatically by 2030. Water stress in the world’s most arid region could worsen, demanding agile responses that integrate digital tools for predictive analytics and climate-smart agriculture.

Emerging trends favor ecosystem-based adaptation, such as restoring green belts in the Sahara for carbon sequestration and biodiversity, which provide social and environmental co-benefits at lower costs than traditional infrastructure. Cross-sectoral ‘nexus’ approaches, linking water, energy, and food security, are on the rise, alongside initiatives like the Great Green Wall spanning over 20 countries to combat desertification. Community-driven strategies, utilizing mobile apps for farmer advisories and renewable energy grids, empower local resilience, while nature-based solutions like managed aquifer recharge address groundwater dependencies.

Finance trajectories are optimistic, with global commitments potentially scaling to meet trillion-dollar needs by mid-century, supported by green bonds and private sector integration. However, equity remains pivotal, ensuring benefits reach North Africa’s rural and vulnerable populations foremost. Pan-Africanism fuels this renaissance, where adaptation evolves into a symbol of unity, harnessing indigenous knowledge and regional cooperation to achieve harmonious balance with nature’s changing patterns.

Unity in the Storm: Synthesizing Pathways for Enduring African Climate Legacy

Weaving together the strands of context, history, consequences, finance, challenges, and trends, North Africa’s climate adaptation odyssey stands as a powerful affirmation of Pan-African resilience. Embracing shared wisdom, innovative spirit, and unwavering solidarity, the region can navigate climatic storms, transforming vulnerabilities into strengths. This demands a steadfast commitment to equity, sustainability, and collaboration, ensuring the sands of North Africa remain a nurturing haven for future generations.