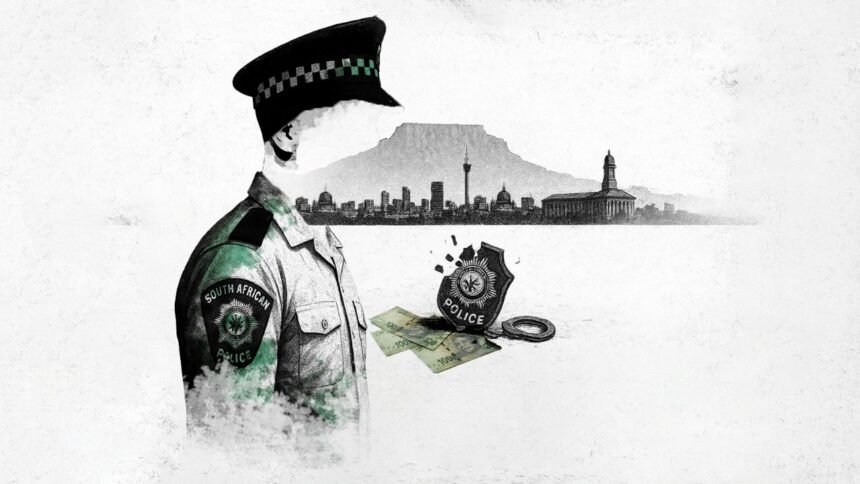

When a former police officer admits to orchestrating a criminal cartel within the nation’s elite crime-fighting unit, and businessmen with ties to underworld networks win hundreds of millions in state contracts, something has fundamentally broken. South Africa is confronting precisely this scenario this week as the Madlanga Commission resumes its investigation into “Operation Takedown,” a secretive police operation that allegedly served criminal interests rather than justice. Crime Intelligence boss Dumisani Khumalo returned to testify on Tuesday as contradictory evidence mounted about the Hawks’ involvement in protecting alleged cartel member Katiso “KT” Molefe, a businessman now imprisoned and connected to networks of organised crime. Meanwhile, the Auditor-General confirmed what investigators had long suspected: the South African Police Service awarded R667.8 million in irregular expenditure, including a controversial R360 million contract to businessman Vousy Musimatlala, currently behind bars and connected to the very criminal enterprises the police were supposedly fighting.

The architecture of this scandal reveals something far more troubling than simple corruption. It suggests a systematic capture of police institutions by organised criminal elements, a penetration so profound that law enforcement entities became mechanisms for protecting and enriching criminals rather than apprehending them. Musimatlala’s company, eMsimango Risk and Security Solutions, received a massive contract for armed security services despite the fact that he was essentially unknown in professional security circles. The Auditor-General’s office identified two specific non-compliance failures: the contract was not advertised within the required 21-day period, and the pre-qualification criteria that should have disqualified Musimatlala were ignored. When investigators checked his credentials, they discovered that the ostensible company owner lacked the basic professional qualifications required for someone managing a security operation for the nation’s police force.

Yet Musimatlala was not alone. Evidence presented to the Madlanga Commission suggests a network of individuals working in concert, using police positions to filter contracts toward preferred vendors, to protect criminal associates, and to redirect law enforcement resources toward protecting their interests rather than serving the public. Brigadier Lee McUa of the Hawks, a senior investigator within the police’s elite detective unit, has reportedly sought legal advice and cannot return to testify at the commission. His absence speaks volumes—a senior police officer participating in an investigation of police corruption who now requires legal counsel before appearing before a public commission investigating police corruption. Other testimony has been contradictory, with witnesses presenting conflicting accounts of phone conversations, meetings, and the nature of investigations supposedly into criminal cartels but operating with a peculiar logic that somehow always protected certain suspects whilst targeting others deemed expendable.

Deputy Minister of Police Shela Boshielo testified before Parliament’s Ad Hoc Committee on Wednesday, becoming the seventh witness to appear before the committee investigating allegations of corruption and criminal capture within the police service. Her testimony was expected to shed light on the functioning of the Political Killings Task Team, an entity supposedly established to investigate politically motivated murders but which has itself become implicated in questions about whether it is functioning as intended or whether it has been compromised to serve political interests. Her colleague, another Deputy Minister, had testified days earlier that despite holding the position for over a year, he had not been delegated any meaningful tasks by his political principal, who has been placed on special leave pending investigations.

What emerges from these hearings is a portrait of institutional dysfunction so profound that it calls into question the capacity of the police service to function as an instrument of justice at all. The Auditor-General identified a pervasive problem: a lack of strong leadership and oversight capable of ensuring compliance with procurement regulations and accurate financial reporting. The National Police Commissioner General Fanni Masimola has publicly acknowledged these failures and stated that he and the Minister of Police have developed a “good working relationship” aimed at addressing these problems. Yet acknowledging failure and remediating it are fundamentally different things. The scale of irregular expenditure, the sophisticated networks apparently operating within police institutions, and the involvement of senior officers in protecting criminal interests suggest that reform will require far more than improved administrative oversight.

The case of Katiso Molefe illuminates what these failures look like in practice. Molefe is alleged to have been connected to criminal cartels operating within South Africa, yet police intelligence assets that should have targeted him instead apparently provided him with protection whilst pursuing his rivals. One commander testified to the commission that he had spoken by phone with a subordinate officer who allegedly provided information suggesting preferential treatment for Molefe. When confronted with evidence, the officer claimed not to remember the conversation, demonstrating the opacity and mutual cover that characterises this alleged conspiracy—individuals deny encounters that witnesses claim occurred, creating a fog through which truth becomes nearly impossible to discern.

For ordinary South Africans trying to have faith in law enforcement, these revelations are deeply corrosive. The police service is meant to be the primary institution through which society enforces rules of law against those who would violate them. When that institution itself becomes captured by the very criminal elements it is supposedly prosecuting, the entire justice system becomes compromised. A citizen who calls the police to report a crime has no assurance that the police will pursue justice impartially. They instead face the possibility that the police are working on behalf of whatever criminal faction has gained influence within the institution.

The Madlanga Commission’s work continues, but already the patterns are clear. Multiple individuals with alleged links to criminality gained access to confidential police information, influence over police investigations, and favourable treatment within law enforcement operations. Contracts worth hundreds of millions were awarded through mechanisms that bypassed basic procurement requirements. Senior officers allegedly used their positions to facilitate criminal activities rather than to combat them. The question facing South Africa’s government is not merely how to hold individuals accountable but whether the police service as an institution can be reformed or whether it has been so thoroughly compromised that rebuilding it may require a more fundamental restructuring than currently under consideration.

In the immediate term, Boshielo’s testimony to Parliament and the ongoing Madlanga Commission proceedings will likely illuminate more details of how extensively police institutions have been captured. Yet each revelation seems to deepen rather than resolve the underlying challenge: South Africa’s law enforcement apparatus appears to have been transformed, at least partially, into a mechanism serving organised crime rather than constraining it. Repairing that damage will require not merely removing corrupt individuals but rebuilding the institutional culture, oversight mechanisms, and ethical frameworks that should have prevented such capture from occurring.