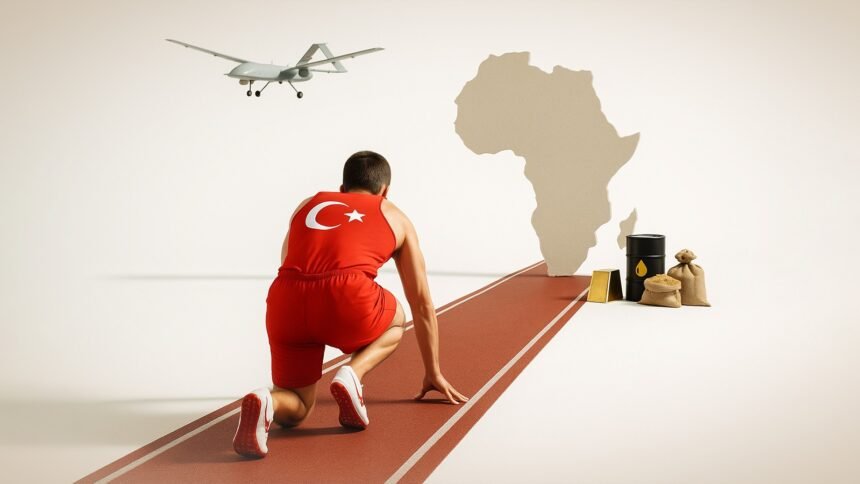

In the grand arena of global geopolitics, where nations vie like athletes in an endless relay, Turkey’s recent sprint into Africa stands out as a bold maneuver. Emerging from the shadows of its Ottoman past, Turkey has repositioned itself as a key player on the continent, weaving threads of diplomacy, trade, military might, and humanitarian gestures into a tapestry that promises partnership but often delivers dependency. This article, rooted in a Pan-Africanist lens that champions continental unity, self-determination, and resistance to external domination, delves into the multifaceted dimensions of Turkey’s engagements. It explores the historical warm-up, current strategies, military incursions, NATO intersections, simmering disputes, and the horizon ahead. Ultimately, it argues that these involvements, while bolstering Turkey’s strategic ambitions and indirectly fortifying NATO’s global posture, come at a profound cost to Africa’s sovereignty, resources, and long-term development, perpetuating a cycle of exploitation under the guise of mutual benefit.

Warming Up on the Historical Track: Ottoman Legacies and Modern Engagements

The roots of Turkey’s involvement in Africa stretch back to the Ottoman Empire. This vast dominion once spanned North Africa and parts of the Horn, positioning itself as both a regional power and a bulwark against European colonial incursions. During the 16th century, Ottoman territories included Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia, Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, and Red Sea provinces like Habesh, where the empire exerted influence over trade routes and local governance. This era saw the Ottomans clashing with European powers, notably during the late 19th-century scramble for Africa, where they sought to counter French ambitions in regions like Senegal and Djibouti. The empire’s presence was not merely militaristic; it involved administrative integration, cultural exchanges, and resistance to colonial penetration in East Africa, where Ottoman alliances with local leaders helped delay the full onslaught of European imperialism.

Yet, this historical footprint was marred by its imperial dynamics—extraction of resources, imposition of governance structures, and suppression of local autonomy—that echoed the very colonialism it ostensibly opposed. The decline of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century, culminating in the Republic of Turkey’s founding in 1923, led to a period of disengagement from Africa. Focused on Western-oriented modernization under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Turkey viewed the continent through a lens of detachment, limiting ties to sporadic diplomatic overtures with newly independent states in the mid-20th century. This aloofness persisted until the late 1990s, when shifting global dynamics prompted a reevaluation.

The turning point came in 2005, declared as Turkey’s “Year of Africa,” marking a strategic pivot under the Justice and Development Party (AKP) leadership. This initiative was driven by a blend of economic opportunism, ideological neo-Ottomanism—a revivalist vision romanticizing the empire’s multicultural legacy—and a desire to diversify alliances beyond Europe and NATO. Diplomatic missions ballooned from a handful to over 40 embassies, fostering summits like the Turkey-Africa Partnership Forums. Trade volumes surged fivefold to around $30 billion annually, encompassing sectors from construction to energy. Turkish contractors undertook massive infrastructure projects: railways in Tanzania, stadiums in Senegal, and airports in Dakar. Humanitarian aid flowed through organizations like the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA), building hospitals, schools, and mosques, often framed as “brotherly” support free from colonial baggage.

From a Pan-Africanist perspective, this resurgence evokes caution. While Turkey positions itself as a non-colonial alternative—unlike France or Britain with their exploitative histories—the neo-Ottoman narrative subtly reasserts dominance. Africa’s post-colonial states, still grappling with the scars of European imperialism, risk swapping one external patron for another. The emphasis on “equal partnership” often masks asymmetrical benefits, where Turkish firms secure lucrative contracts while African labor and resources fuel Ankara’s growth. This historical context sets the stage for contemporary plays, where Turkey’s engagements, though innovative, perpetuate a dependency model that undermines Pan-African ideals of self-reliance and unity.

Building the Stadium: Diplomatic and Economic Plays in Africa’s Arena

Turkey’s diplomatic offensive in Africa resembles a well-orchestrated team strategy, expanding its influence through soft power tools that blend economics, culture, and ideology. Over the past two decades, Ankara has signed numerous agreements spanning trade, investment, and development, positioning itself as a bridge between Asia, Europe, and Africa. Turkish Airlines now connects over 60 African destinations, facilitating not just travel but business flows. Economic ties have deepened in resource-rich regions: oil and gas exploration off Somalia’s coast, uranium interests in Niger, and agricultural partnerships in East Africa. By 2023, Turkish investments in African projects exceeded $85 billion, with firms like those in the construction sector transforming skylines and infrastructure.

Culturally, Turkey leverages shared Islamic heritage, funding mosques and religious institutions via the Diyanet Foundation, while educational exchanges bring thousands of African students to Turkish universities on scholarships. Media outreach, including broadcasts in local languages, promotes a narrative of solidarity. In West Africa, power plants and renewable energy initiatives address chronic shortages, earning goodwill. In the Horn, mediation efforts—such as brokering cease-fires in Libya or facilitating talks between Ethiopia and Somalia—cast Turkey as a peacemaker.

However, this stadium-building comes with hidden costs. Economically, while projects create jobs, they often import Turkish labor and materials, limiting technology transfer and local capacity building. Trade imbalances favor Turkey, with Africa exporting raw commodities and importing finished goods, echoing colonial patterns. Diplomatically, Turkey’s push aligns with its broader ambition to elevate its global status, using Africa as a voting bloc in international forums like the UN. Pan-Africanists see this as a subtle form of neo-imperialism: Africa’s vast untapped resources—60% of the world’s arable land, 30% of minerals—become pawns in Turkey’s quest for energy security and market expansion. The “win-win” rhetoric belies how these engagements reinforce Africa’s peripheral role in global value chains, hindering the continent’s industrial leapfrog toward unity and autonomy.

The Military Relay: Bases, Drones, and Security Gambits

No aspect of Turkey’s African foray is more contentious than its military expansion, akin to a high-stakes relay where bases and arms deals hand off influence across the continent. Turkey’s largest overseas military facility, TURKSOM in Mogadishu, Somalia, established in 2017, trains thousands of Somali troops and houses up to 2,000 personnel. This presence extends to drone supplies: Bayraktar TB2 unmanned aerial vehicles have been exported to over a dozen African nations, including Ethiopia, Libya, and Niger, for counter-terrorism operations. Recent developments include taking control of the Abéché base in Chad following France’s withdrawal, and agreements in Libya for military cooperation.

These moves are framed as supportive: aiding fragile states against insurgents like al-Shabaab in Somalia or stabilizing post-conflict zones. Turkey’s defense pacts with countries like Kenya, Rwanda, and Nigeria emphasize training and equipment, filling voids left by retreating Western powers. In the Sahel, where juntas have expelled French forces, Turkey steps in with affordable, effective weaponry, positioning itself as a reliable partner against jihadist threats.

Yet, this relay raises red flags for Pan-African unity. Military bases entrench foreign presence, potentially serving Turkish interests over African ones. Drone sales, while empowering local forces, escalate conflicts and dependency on Turkish maintenance and intelligence. In the Horn, Turkey’s mediation in Ethiopia-Somalia tensions masks its strategic gains, like offshore energy rights. From a Pan-Africanist viewpoint, this militarization fragments the continent, prioritizing bilateral deals over collective security frameworks like the African Union’s Peace and Security Architecture. It benefits Turkey by expanding its defense industry exports and geopolitical leverage, but at Africa’s expense, where external arms fuel internal divisions and divert resources from development.

NATO’s Team Huddle: Alliance Crossovers in the Continental League

As a NATO member since 1952, Turkey’s African ventures intersect with the alliance’s evolving southern flank strategy, creating a team dynamic that amplifies Western influence. NATO’s interest in Africa has grown amid threats like terrorism, migration, and great-power competition from Russia and China. Turkey’s approach—combining military aid, diplomacy, and development—offers a model for NATO to fill vacuums left by France’s waning footprint in the Sahel or U.S. retrenchment.

In practice, Turkish operations align with NATO goals, including stabilizing Libya to curb migration flows to Europe, countering Russian Wagner (now known as Africa Corps) in Mali and Niger, and securing maritime routes vital for alliance logistics. Contributions to UN and NATO missions in Africa, alongside bilateral agreements, enhance interoperability. Turkey’s mediation in Sudan or Somalia indirectly supports NATO’s counter-terrorism agenda, providing intelligence and operational support without direct alliance branding.

However, this huddle benefits NATO disproportionately. By leveraging Turkey’s non-Western image, the alliance extends its reach without the baggage of direct intervention, maintaining plausible deniability. For Turkey, NATO membership legitimizes its actions, granting access to technology and alliances that bolster its African push. Pan-Africanists argue this crossover perpetuates imperial dynamics: Africa’s security challenges become pretexts for NATO’s containment of rivals, sidelining African-led solutions. The continent pays the price in sovereignty erosion, as foreign bases and arms deals entangle local politics in transatlantic rivalries, hindering the dream of a united, self-defending Africa.

Fouls and Red Cards: Disputes and Tensions on the Pitch

Turkey’s African engagements are not without faults, as disputes highlight the frictions of unequal power. In the Horn, Turkey’s support for Somalia in maritime disputes with Kenya, as well as its mediation between Ethiopia and Somalia, has drawn accusations of favoritism, exacerbating regional rivalries. Perceptions of neo-Ottomanism—reviving imperial designs—linger in North Africa, where historical Ottoman rule evokes mixed sentiments in Algeria and Tunisia.

Economic grievances include contract disputes and labor exploitation by Turkish firms, while military deals raise concerns over human rights abuses enabled by drones in conflict zones. In Chad and Niger, base takeovers following the French exit spark fears of new dependencies. These tensions fragment African unity, as bilateral ties pit nations against each other in alignment games.

Pan-Africanists view these flaws as evidence of exploitation: Turkey’s gains in resources and influence come amid Africa’s vulnerabilities, deepening divisions rather than fostering solidarity.

Crossing the Finish Line: Future Prospects and Pan-Africanist Warnings

Looking ahead, Turkey’s African marathon shows no signs of slowing. Projections indicate trade doubling, more bases in the Sahel, and expanded mediation roles. With Africa’s demographic boom—1.4 billion people by 2050—and resource wealth, Turkey eyes long-term partnerships in energy, infrastructure, and space (e.g., a Somali spaceport). Yet, risks abound: overextension could strain Turkey’s economy, while African pushback against foreign militaries grows.

The future outlook hinges on Africa’s agency. If engagements evolve toward genuine technology transfer and equitable trade, benefits could accrue continent-wide. However, current trajectories suggest continued asymmetry, with Turkey—and, by extension, NATO—scoring geopolitical goals while Africa lags behind.

In conclusion, Turkey’s involvements in Africa, though cloaked in partnership, primarily advance Ankara’s ambitions and NATO’s strategic depth at the continent’s expense. This neo-imperial relay extracts resources, militarizes landscapes, and fragments unity, echoing colonial marathons of old. Pan-Africanism demands a red card: Africa must unite to redefine the game, prioritizing self-determination over external patrons. Only then can the savanna become a field of sovereign triumphs, not foreign victories.