Introduction: The Dawn of African Liberation

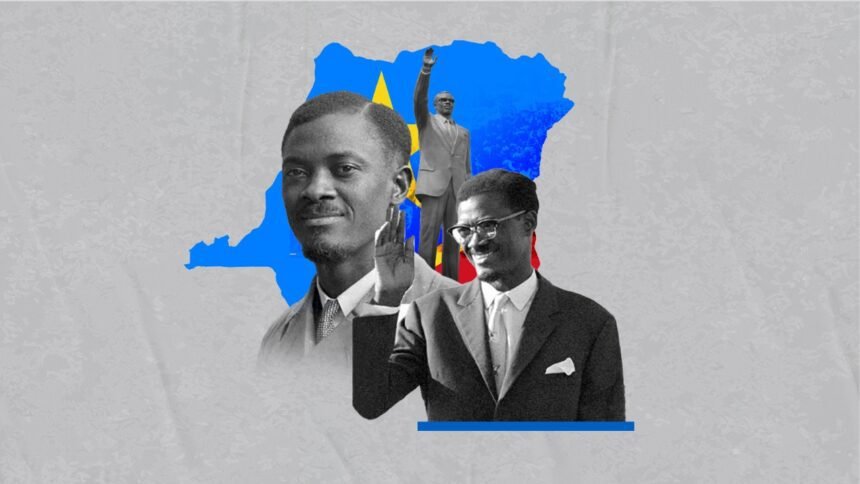

In the mid-20th century, Africa stood on the cusp of monumental change as the tides of decolonization surged across the continent. The Belgian Congo, a vast territory endowed with immense natural wealth yet burdened by decades of oppressive colonial rule, emerged as a critical battleground for African self-determination and global geopolitical rivalries. At the forefront of this struggle was Patrice Émery Lumumba, a charismatic and visionary leader whose tenure as the first Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) encapsulated the dreams and trials of a newly independent Africa. Lumumba’s fierce dedication to national sovereignty, social equity, and the unification of African nations positioned him as a towering figure in the fight against imperialism. His tragic assassination in 1961, a plot orchestrated by foreign powers with local complicity, cemented his status as a martyr for African liberation. This article explores Lumumba’s life, his pivotal role in Congo’s independence, his pan-African ideals, and the enduring resonance of his legacy across the continent and beyond.

The Shadow of Colonialism: Congo Under Belgian Rule

The Belgian Congo (1908–1960) bore the scars of one of the most exploitative colonial regimes in history, a legacy that began with King Leopold II’s Congo Free State (1885–1908). Under Leopold’s rule, the Congolese endured forced labor, mass atrocities, and the plundering of resources like rubber and ivory, resulting in the deaths of millions. When Belgium assumed direct control in 1908, the exploitation persisted, albeit under a more structured colonial administration. The Congolese were denied political agency, subjected to economic servitude, and offered only rudimentary education designed to produce a compliant workforce rather than an enlightened citizenry. By the 1950s, the global wave of decolonization—sparked by events such as Ghana’s independence in 1957 under Kwame Nkrumah—had ignited nationalist fervor in Congo. Political organizations proliferated, among them the Congolese National Movement (MNC), founded by Lumumba in 1958. The MNC stood out for its rejection of ethnic fragmentation and its call for a unified, independent Congo, setting the stage for Lumumba’s rise as a transformative leader.

| Aspect | Details |

| Colonial Period | Belgian Congo (1908–1960), preceded by Congo Free State (1885–1908). |

| Exploitation | Forced labor, resource extraction (rubber, minerals), millions died. |

| Education | Limited, focused on manual skills; few Congolese accessed higher education. |

| Decolonization Wave | Inspired by Ghana’s 1957 independence; rise of nationalist movements. |

| Key Political Party | Congolese National Movement (MNC), founded by Lumumba in 1958. |

From Village to Vanguard: Lumumba’s Early Years and Intellectual Awakening

Patrice Lumumba was born on July 2, 1925, in the village of Onalua in Kasai province, to a family of the Tetela ethnic group. Raised in a modest Catholic household, he attended mission schools run by both Protestant and Catholic educators, where he absorbed a blend of traditional Congolese values and Western intellectual traditions. A voracious learner, Lumumba taught himself multiple languages—French, Tetela, Lingala, Swahili, and Tshiluba—demonstrating an early aptitude for communication that would later define his political career. His professional life began with humble roles: a nursing assistant, a beer salesman, and eventually a postal clerk in Stanleyville (now Kisangani) and Leopoldville (now Kinshasa). These experiences exposed him to the stark inequalities of colonial society. In 1950, he established the Comité de l’Union Belgo-Congolaise, initially seeking reform within the colonial framework. However, his arrest in 1956 on trumped-up charges of embezzlement radicalized him, turning his focus toward complete independence. Influenced by Enlightenment thinkers like Rousseau and Voltaire, as well as African nationalist writers, Lumumba’s early essays and poetry laid the intellectual groundwork for his revolutionary ideals.

The Rise of a Nationalist Leader: Lumumba’s Political Journey

Lumumba’s political career took off with the founding of the Congolese National Movement (MNC) in 1958, a party that championed national unity over ethnic division—a bold stance in a country with over 200 distinct ethnic groups. The MNC’s platform called for social justice, economic self-reliance, and an end to colonial domination, resonating widely among the Congolese populace. In December 1958, Lumumba attended the All-African People’s Conference in Accra, Ghana, hosted by Kwame Nkrumah. This gathering of African leaders galvanized his commitment to pan-Africanism, the belief in a united Africa free from colonial shackles. Back in Congo, his fiery speeches, such as the one delivered in Stanleyville in 1959, which incited a riot, showcased his ability to mobilize the masses. However, it led to his brief imprisonment. Released to participate in the 1960 Brussels Round Table Conference, Lumumba negotiated Congo’s independence terms. In May 1960, the MNC secured a parliamentary majority, and Lumumba was appointed Prime Minister alongside President Joseph Kasavubu. His iconic independence speech on June 30, 1960, denounced Belgian colonialism and proclaimed, “We are no longer your monkeys,” a declaration that reverberated across Africa as a call for dignity and self-rule.

| Event | Details |

| MNC Formation | Founded in 1958, led by Lumumba, aimed for national unity and independence. |

| Accra Conference | 1958, met Nkrumah, embraced pan-Africanism. |

| Elections | May 1960, MNC won most seats; Lumumba appointed Prime Minister. |

| Independence Speech | June 30, 1960, criticized colonial rule, called for unity and justice. |

A Vision Beyond Borders: Lumumba’s Pan-Africanism and Global Outlook

Lumumba’s ambitions extended far beyond Congo’s frontiers. He envisioned a united Africa, a continent where nations would collaborate to overcome the legacies of colonialism and assert their collective strength on the global stage. His interactions with contemporaries like Nkrumah of Ghana, Ahmed Sékou Touré of Guinea, and Julius Nyerere of Tanzania reinforced this pan-Africanist ethos. At home, he sought to harness Congo’s vast resources—copper, cobalt, and diamonds—for the benefit of its people, rather than for the benefit of foreign corporations. However, his internationalist outlook drew him into the vortex of Cold War politics. Lumumba’s refusal to align unequivocally with either the United States or the Soviet Union, coupled with his request for UN assistance during the Congo Crisis, alienated Western powers. His vision of a non-aligned, self-sufficient Africa threatened neocolonial interests, setting the stage for his eventual downfall.

The Congo Crisis: Betrayal, Chaos, and Martyrdom

Independence brought immediate turmoil to Congo. Just days after June 30, 1960, the army mutinied, and the mineral-rich province of Katanga, backed by Belgian and Western interests, seceded under the leadership of Moïse Tshombe. Lumumba appealed to the United Nations for support. Still, their reluctance to intervene decisively prompted him to seek Soviet aid—a move that alarmed the United States and its allies amid Cold War paranoia. Internally, tensions with President Kasavubu and military chief Joseph-Désiré Mobutu (later Mobutu Sese Seko) escalated. In September 1960, Kasavubu dismissed Lumumba, who in turn declared Kasavubu’s action. Ditto, Mobutu staged a coup, arresting Lumumba in December 1960. Transferred to Katanga in January 1961, Lumumba was brutally assassinated on January 17, alongside aides Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito, with evidence pointing to CIA and Belgian involvement. The Congo Crisis spiraled into decades of instability, a direct consequence of the power vacuum left by Lumumba’s death.

Echoes of a Dream: Lumumba’s Legacy in Congo and Beyond

Lumumba’s assassination did not extinguish his ideals; it amplified them. In the DRC, he remains a national hero; his image adorns public spaces, and his name is invoked in struggles for justice and sovereignty. Across Africa, his pan-Africanist vision inspired liberation movements, from Algeria’s FLN to South Africa’s ANC. Leaders like Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso and Nelson Mandela cited Lumumba as a symbol of resistance against neocolonialism. Globally, his legacy continues to fuel debates about imperialism and self-determination, with scholars and activists lauding his courage while critics question his pragmatic approach to leadership. In 2002, Belgium formally apologized for its role in his death. Yet, the scars of his loss endure in Congo’s ongoing challenges—conflict, poverty, and foreign exploitation—underscoring the unfulfilled promise of his dream.