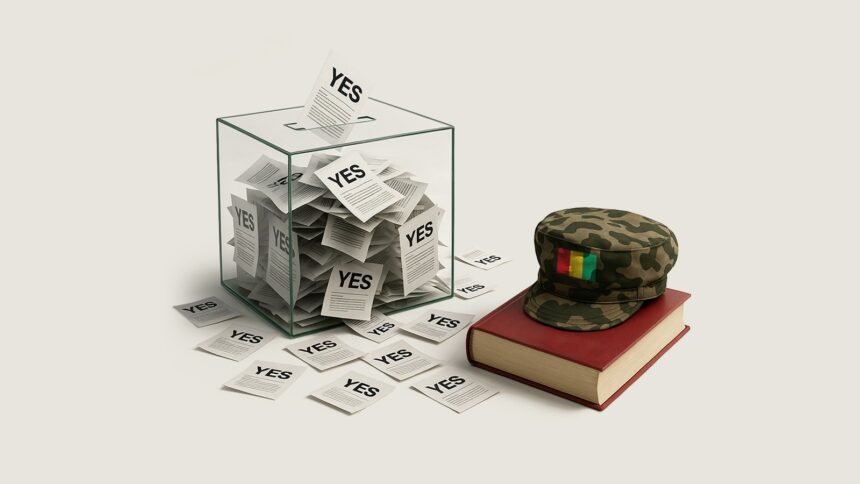

Guinea’s military rulers have gotten what they wanted: a resounding “yes” from voters to a brand-new constitution. With more than 90 percent of votes counted, over 90 percent of them are in favour. It’s a landslide that will allow coup leader Mamady Doumbouya, who grabbed power in 2021, to stand for president and potentially extend his stay far beyond what was promised when he first appeared in fatigues and sunglasses, toppling Alpha Condé’s civilian government.

The results, released by the electoral authority late Monday, were greeted by the junta as a “victory for the Guinean people.” Streets in Conakry saw flag-waving supporters dancing and blaring horns. State TV ran wall-to-wall coverage of “historic participation,” celebrating a turnout north of 70 percent.

But outside the tightly controlled capital, the mood is more mixed. Opposition parties, many of which are banned or in exile, say the entire exercise was a rubber stamp with no real competition. Media restrictions were heavy, rallies opposing the draft were blocked, and several activists were detained. “This was not a referendum — it was a ritual of approval,” one opposition spokesman told reporters from Dakar, calling the process “designed to legitimise military power, not return the country to civilian rule.”

At the heart of the debate is the constitution’s controversial Article 42, which clears the way for Doumbouya to contest elections as a civilian candidate once he formally steps down as head of the junta. For critics, this is the oldest trick in the coup leader’s playbook: promise a transition, then rewrite the rules so you can stay. For Doumbouya’s camp, it’s simply giving Guineans a chance to choose continuity. “We are not clinging to power; we are laying a new foundation,” he told a packed hall last week.

The wider region is watching closely. West Africa has been battered by successive coups — Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger — and ECOWAS has struggled to get any of these military regimes back onto a civilian timetable. Guinea’s referendum could now be a blueprint for others: hold a vote, claim legitimacy, and reset the political clock. That worries some democracy advocates, who fear the region is normalising military takeovers as just another route to power.

The economic picture complicates things further. Guinea is rich in bauxite and other minerals, making it a key supplier for the global aluminium industry. International investors have stayed relatively quiet, worried more about stability than about the form of government. If Doumbouya’s new constitutional order keeps the mines running and the ports open, there may be little pressure from major partners like China, which buys a large share of Guinea’s bauxite.

Ordinary Guineans, meanwhile, are left to weigh pragmatism against principle. Some argue that the junta has at least restored a measure of security, repaired roads, and begun tackling graft. Others say freedoms have shrunk, and dissent has become dangerous. The truth may lie somewhere in between: Guinea has not descended into chaos, but neither has it charted a clear path to an open democracy.

Analysts point out that referendums with such lopsided results often say more about the system than the voters. In competitive democracies, 90 percent margins are rare. Here, they are a reminder that the playing field was tilted. And yet, many Guineans genuinely did vote yes — hoping that constitutional stability will finally end decades of coups and countercoups.

What happens next will be telling. The junta has promised elections within 18 months under the new framework. If those polls are free and fair, Doumbouya may indeed secure a popular mandate. If not, Guinea risks returning to the cycle it knows too well: protests, repression, and eventually, another power grab.

For now, though, Conakry is in celebration mode. The regime has its constitution, its landslide, and its roadmap. Whether that roadmap leads to democracy or just a more comfortable military presidency is the question Guineans — and the rest of West Africa — will be asking for months to come.