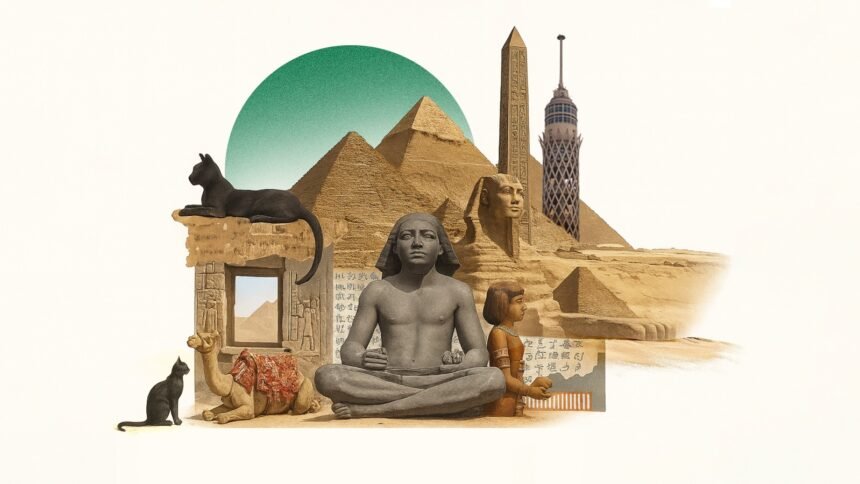

From the shadow of the pyramids to the hum of Al-Darb al-Ahmar’s workshops, Cairo remains Africa’s greatest living manuscript—a city of twenty-five million souls where pharaonic dust still settles on Mamluk domes, where pigeon towers crown concrete rooftops, and where craft, memory, and urban life refuse every attempt at separation.

Nile’s Endless Palimpsest: Urbanism as Layered Memory

Founded in 969 CE as the Fatimid capital Al-Qāhirah—“the Victorious”—Cairo never erases; it overwrites. Coptic fortresses cradle Fatimid gates, Ayyubid citadels shelter Mamluk madrasas, Ottoman sabils lean against French-era balconies, and twenty-first-century apartments sprout satellite dishes beside ninth-century minarets. The Nile, the original master-planner, once dictated settlement through its flood cycle; today its banks host informal boat-yards where wooden feluccas are still caulked by hand. This is place-making through accretion rather than demolition—an African urban philosophy that treats history as raw material for continual reinvention rather than relic to be frozen behind glass.

City of the Living Dead: Radical Inclusion in the Necropolis

The Southern Cemetery—known locally as the City of the Dead—stretches for six kilometres along the Mokattam hills and offers one of the continent’s boldest lessons in inclusive urbanism. Since the seventh century, families have lived among tombs; today, over half a million Cairenes call this necropolis home. Marble-cutters saw blocks beside Mamluk mausolea, children play football in the courtyards of fifteenth-century khanqahs, and silk-rope makers stretch their wares down streets laid before the Crusades. The monumental complex of Sultan al-Nasir Faraj ibn Barquq (1400–1411) stands at its heart: mosque, school, and hospice fused into a single breathing organism whose roof still offers one of the city’s most sublime panoramas. Here, death is not segregated from life but woven into its daily fabric—an African understanding that memory is most alive when it is inhabited.

Craft as Living Commons: Knowledge Beyond Copyright

In the narrow lanes of Al-Darb al-Ahmar, more than a thousand artisans continue traditions that predate the Renaissance. Tent-makers stitch appliqué khayameya beneath medieval arches; bronze founders pour molten metal in courtyards once used by Mamluk armourers; glassblowers fire recycled bottles into lanterns that will hang in Ramadan streets. This is not a museum quarter but a functioning guild ecology grounded in radical openness: a passer-by who pauses to watch a copper engraver is offered tea, then tools, then three hours of unhurried tuition. Knowledge here is common property, passed hand-to-hand rather than locked in patents or diplomas. Young designers—Egyptian, Sudanese, European-born—now rent tiny workshops among these masters, learning to carve alabaster beside men whose grandfathers carved for mosques. The result is a slow, generative modernism that grows from the street rather than descending from academies.

Mud-Brick Renaissance: Vernacular Futures

Hassan Fathy’s revolution continues to ripple. In the 1940s, he demonstrated that mud brick—material of the living, not the eternal dead—could create vaulted villages of breathtaking elegance at New Gourna near Luxor. His former Cairo residence, now the Egyptian Architecture House, displays delicate plaster models that showcase Mamluk geometry meeting Nubian vaulting techniques. A generation later, Ramses Wissa Wassef founded the adobe arts compound at Harrania on the Giza plateau, where village children learned tapestry without formal instruction and produced work now exhibited worldwide. Today, the same compound hosts young stone-carvers from Upper Egypt shaping contemporary furniture, alongside weavers whose patterns still carry pharaonic lotus motifs. These are not heritage reconstructions but living laboratories proving that climate-responsive, labour-intensive building cultures remain viable—and beautiful—in the twenty-first century.

Sacred Space, Profane Embrace: Ibn Tulun and the Art of Coexistence

The ninth-century Mosque of Ahmad ibn Tulun stands as Africa’s oldest intact large-scale mosque and perhaps its most profound essay on spatial generosity. Its vast brick courtyard—large enough to host an entire neighbourhood—absorbs the chaos that presses against its walls: apartment blocks lean on its crenellations, laundry flutters above its arcades, and the call to prayer rises above the roar of microbuses. Climb the tulip-shaped minaret at sunset, and the entire city spreads beneath you—ancient, modern, orderly, anarchic—held together not by zoning laws but by the quiet authority of shared space. This is urbanism that refuses the modernist urge to separate the sacred from the everyday, the monument from the mess.

Pan-African Crucible: Cairo as Continental Atelier

Though sometimes tempted to look only north, contemporary Cairo is reasserting its place as Africa’s creative lung. Malian potters would recognise the open-handed teaching in Al-Darb al-Ahmar; Ethiopian highland weavers share aesthetic DNA with Harrania’s tapestries; Great Zimbabwe’s dry-stone mastery finds contemporary echo in Fathy-inspired adobe vaults. When a Danish-Egyptian designer chooses Cairo over Copenhagen, when Sudanese marble-carvers ship blocks to Giza workshops, when Tunisian ceramicists fire alongside Nubian descendants, the city becomes a working laboratory for an emerging Pan-African aesthetic—one that honours deep time while improvising fearless futures.

In Cairo, architecture is never a finished object. It is a social contract, a pedagogical device, an economic engine, and a poetic act. The city teaches a profound African lesson: authentic place-making does not tame chaos but cultivates the conditions in which generosity, skill, and collective memory can continually renew themselves. As the continent reclaims authority over its urban narratives, Cairo—vast, contradictory, magnanimous—stands not as a model to imitate but as a method to inhabit: lean into the layers, trust the knowledge that flows in the streets, and let the city keep writing its endless, living text through every hand that chooses to stay.