Across the expansive horizons of Africa, where the Sahara’s golden dunes meet the lush canopies of the Congo Basin, and ancient trade routes echo with the footsteps of resilient forebears, maps have historically been more than mere drawings—they are narratives of power, identity, and survival. For African women, who have long been the backbone of communities as farmers, healers, traders, and storytellers, these maps often tell a story of omission, where their vital roles are sidelined in favor of dominant, patriarchal viewpoints. This comprehensive exploration delves into the multifaceted saga of women’s representation in mapping within Africa, weaving together the rich historical threads, the layered contextual realities, the persistent and intersecting challenges, the bold acts of feminist space-making, and the luminous visions for a future grounded in equity. Drawing from a Pan-Africanist vision that unites the continent’s diverse peoples in collective self-determination and a feminist framework that amplifies women’s voices as agents of change, this narrative positions African women not as footnotes in cartographic history but as the masterful cartographers charting paths toward liberation, sustainability, and communal flourishing.

Ancestral Blueprints and Colonial Shadows: Unraveling the Historical and Contextual Layers of Gendered Cartography in Africa

The genesis of mapping in Africa is deeply intertwined with indigenous epistemologies, where knowledge of the land was passed down through generations in forms far removed from Western paper charts. In matriarchal societies like those of the Ashanti in Ghana or the Berber communities in North Africa, women were the keepers of spatial wisdom, mapping invisible boundaries through songs, dances, and communal rituals that marked fertile grounds, water sources, and migration paths essential for survival. These organic maps embodied a holistic understanding of the environment, incorporating not just physical features but also spiritual and social dimensions, such as sacred groves protected by women’s guilds or trading networks sustained by female entrepreneurs along the Swahili coast.

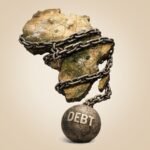

The intrusion of colonialism shattered this equilibrium, imposing rigid, extractive cartographies that served imperial agendas. European powers redrew Africa’s borders with arbitrary lines during the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, ignoring ethnic, cultural, and gender dynamics, which disproportionately marginalized women. Post-colonial states inherited these skewed systems, where modern geospatial tools—ranging from satellite imagery to digital platforms—continued to perpetuate exclusions. In contemporary Africa, with its population exceeding 1.4 billion and women comprising roughly half, the geospatial landscape reveals stark disparities. Women, who perform up to 75 percent of agricultural labor in regions like East Africa, often find their contributions unmapped, leading to policies that overlook their needs in land tenure, resource allocation, and climate resilience.

Contextually, this invisibility is exacerbated by intersecting factors such as urbanization, climate change, and economic globalization. In rapidly growing cities like Lagos in Nigeria or Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, informal settlements—home to millions of women-led households—remain under-mapped, heightening vulnerabilities to floods, evictions, and health crises. For instance, during the 2022 floods in Durban, South Africa, inadequate mapping of drainage systems and safe zones left women, who are primary caregivers, disproportionately affected, scrambling to protect families without reliable data. Similarly, in arid zones of the Sahel, where desertification threatens livelihoods, women’s knowledge of drought-resistant crops and water conservation is not recorded in official maps, undermining adaptation efforts. The rise of digital mapping platforms, while promising, often amplifies these gaps; global datasets like Google Maps or OSM draw from crowdsourced inputs that are predominantly male, with women’s participation hampered by literacy barriers, internet access limitations (only about 40 percent of African women have reliable connectivity), and cultural norms that confine them to domestic spheres. Yet, this context also breeds opportunity, as emerging African-led initiatives begin to reclaim these tools, integrating women’s perspectives to foster more inclusive representations of the continent’s diverse terrains—from the highlands of Lesotho to the riverine deltas of the Niger.

Breaking the Invisible Barriers: Intersecting Challenges in Amplifying African Women’s Voices in Geospatial Domains

The journey toward equitable representation in mapping is akin to traversing Africa’s rugged escarpments, where every step forward encounters formidable obstacles rooted in systemic inequalities. At the forefront is the pervasive digital divide, which intersects with gender, class, and geography. In rural areas of countries like Uganda or Zimbabwe, where electricity and broadband are luxuries, women face compounded exclusions; they juggle multiple roles—farming, child-rearing, and household management—leaving scant time for engaging with mapping technologies. Participatory projects, though well-intentioned, often see low female turnout; for example, in mapathons organized across the continent, women might represent only 20-30 percent of participants, deterred by travel costs, safety concerns, or lack of childcare support.

Data biases further entrench these challenges, creating maps that are blind to women’s realities. Features crucial for gender equity, such as breastfeeding stations in public spaces, pathways free from harassment, or markets where women dominate informal trade, are frequently absent. This omission has dire consequences in humanitarian contexts; during Ebola outbreaks in West Africa or ongoing conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo, unmapped health facilities and escape routes heighten women’s risks of violence and disease. Economic dimensions add another layer: with women owning less than 20 percent of titled land continent-wide, geospatial data fails to capture their informal land use, perpetuating disputes and dispossession amid large-scale land grabs by multinational corporations.

Societal and institutional hurdles compound the issue, from patriarchal norms that devalue women’s expertise to underfunded programs in women’s ministries. In conflict-ridden areas like Somalia or South Sudan, where women endure the brunt of displacement (comprising up to 70 percent of refugees), mapping efforts are disrupted by insecurity. Yet, their insights into safe corridors and resource hubs remain untapped. Environmental pressures, such as deforestation in Madagascar or water scarcity in Namibia, disproportionately burden women as primary resource gatherers, but climate maps rarely incorporate their adaptive strategies. These multifaceted challenges highlight a broader continental paradox: Africa boasts innovative tech hubs in places like Rwanda’s Kigali or Kenya’s Silicon Savannah, yet without deliberate gender inclusion, geospatial advancements risk reinforcing old hierarchies, leaving women as spectral figures on the digital landscape.

Forging Feminist Frontiers: African Women’s Audacious Acts of Space-Making in Cartographic Revolutions

Undeterred by these adversities, African women are reclaiming the geospatial arena through audacious, community-rooted innovations that embody feminist solidarity and Pan-African resilience. This space-making is a form of radical praxis, where women transform exclusionary tools into vehicles for empowerment, prioritizing collective well-being over individual gain. Grassroots movements, such as those led by women’s cooperatives in Senegal’s Casamance region, have pioneered community mapping to document mangrove ecosystems, integrating women’s knowledge of sustainable fishing and herbal medicine to combat coastal erosion.

Networks like the African Women in GIS collective serve as vital incubators, offering training and mentorship that equip women with skills in remote sensing and data visualization. In Tanzania, initiatives like Crowd2Map have mobilized women to map rural villages, tagging schools, clinics, and safe houses to prevent female genital mutilation, turning digital platforms into shields against cultural harms. Similarly, in Zambia, women’s groups have collaborated with HOT to create detailed maps of maternity shelters, ensuring that expectant mothers in remote areas receive timely care, blending technology with traditional midwifery wisdom.

Urban contexts showcase equally transformative efforts. In Nairobi’s Kibera slum, women-led mapping teams have documented water points and sanitation facilities, advocating for infrastructure improvements that reduce the time women spend fetching water—from hours daily to minutes—freeing them for education and entrepreneurship. Continental collaborations, such as Open Cities Africa’s projects in multiple countries, have trained thousands, with women at the helm designing gender-sensitive urban plans that address mobility and safety. These endeavors extend to advocacy, where tools like interactive dashboards in South Africa track gender-based violence hotspots, informing policy reforms. By weaving together technology, activism, and cultural heritage, African women are not just adding data points; they are redrawing the continent’s narrative, echoing the spirit of liberation icons like Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, who mapped paths to freedom through unyielding resistance.

Horizons of Harmony: Envisioning a Pan-African Feminist Future in Geospatial Equity

As the sun rises on Africa’s evolving geospatial landscape, the future holds boundless promise for women’s full integration, fueled by innovation, unity, and unwavering optimism. Collaborative ecosystems, bridging governments, NGOs, and tech innovators, can amplify women’s roles through targeted investments in education and infrastructure. Imagine a continent where AI-driven mapping platforms, customized for African contexts, automatically incorporate gender-disaggregated data, predicting and mitigating risks like droughts in Botswana or urban sprawl in Egypt with women’s inputs at the core.

Aspirations include expanding networks like YouthMappers to include more women-focused chapters, fostering mentorship that spans borders—from Morocco’s tech-savvy youth to Lesotho’s rural innovators. In high-achieving nations like Rwanda, where women hold over 60 percent of parliamentary seats, geospatial policies could set benchmarks, using satellite data to secure land rights and promote agroecology led by female farmers. Addressing persistent gaps, future efforts might leverage mobile apps tailored for low-literacy users, enabling women in Mali’s remote villages to contribute via voice inputs, mapping nomadic routes and cultural sites.

This visionary path acknowledges enduring hurdles but embraces hope through solidarity. By centering African women’s expertise, geospatial futures can drive economic revolutions, such as in Liberia’s mining sectors, where mapped resources ensure fair benefits for women artisans. Ultimately, this era will see African women as the vanguard of a unified, equitable cartography, where maps reflect the continent’s true essence: a mosaic of strength, diversity, and shared destiny, ensuring every sister’s story is etched indelibly into the Motherland’s enduring atlas.