If you had a sense of déjà vu reading the headlines from Chad this week, you’re not alone. In a move that has become eerily familiar across parts of Africa, Chad’s transitional government has officially scrapped presidential term limits — again — clearing the path for Mahamat Idriss Déby to stay in power well beyond 2030. The vote, carried out by the National Transitional Council, was presented as a “necessary step toward stability,” but to critics it smells suspiciously like democracy on pause.

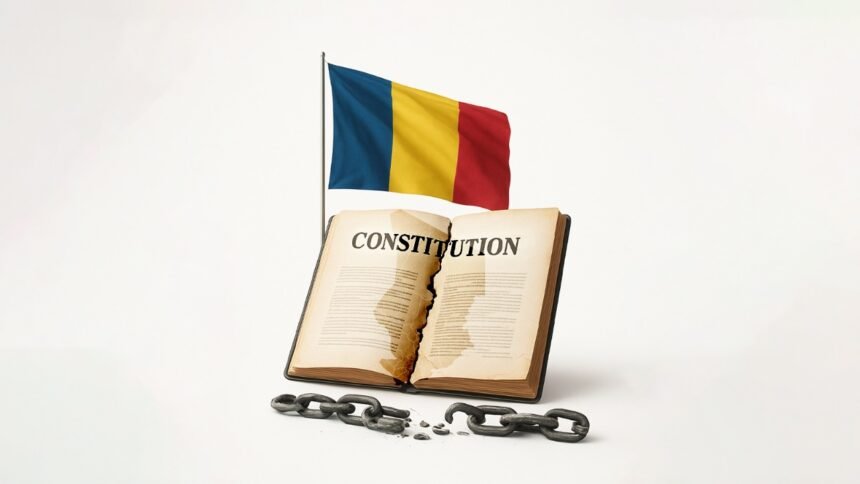

The decision comes three years after Mahamat, son of the late strongman Idriss Déby, seized power following his father’s death on the battlefield. At the time, he promised a short transition, free elections, and a return to civilian rule. “We will not cling to power,” he said in 2021. But the script has since been revised, rewritten, and now tossed in the trash. The new constitution approved earlier this year already concentrated significant powers in the presidency. The latest amendment finishes the job by removing the two-term limit, which was a hard-won reform of the 2018 constitution.

For supporters, this is about avoiding chaos in a country that has been a linchpin in the fight against jihadist insurgencies in the Sahel. Chad’s army is one of the region’s most battle-hardened forces, and foreign powers — particularly France — have long leaned on N’Djamena as their security partner. “Continuity is crucial,” said one government spokesman, arguing that Déby’s leadership is the glue holding together a country beset by rebel groups, communal clashes, and economic malaise. The government insists that elections scheduled for 2026 will still happen, though with the playing field now heavily tilted toward the incumbent.

Opposition voices, however, see a familiar pattern. “This is not a transition, it is a coronation,” said Succes Masra, a leading opposition figure who has already clashed with the regime. Civil society groups warn that extending Déby’s stay risks fuelling unrest, especially in a country where youth unemployment is sky-high and frustration simmers under the surface. Memories are still fresh of the October 2022 protests that turned deadly when security forces cracked down on demonstrators demanding a quicker return to civilian rule.

The international community’s reaction has been cautious, almost muted. France, Chad’s former colonial power and closest ally, offered a bland statement encouraging dialogue and inclusivity. The African Union, which once championed “zero tolerance” for military takeovers, has been largely silent. Analysts say the geopolitical stakes are simply too high: Chad hosts French troops and is a bulwark against jihadist groups threatening the region. Few outside actors are willing to risk rocking the boat.

The move also places Chad squarely in a club of African nations where constitutions seem to bend to presidential ambition. Rwanda, Uganda, Cameroon, Congo-Brazzaville — all have leaders who extended their rule by scrapping term limits. The pattern is so common it has a nickname: “constitutional coups.” Critics argue that they are just as corrosive to democracy as military putsches, if not more so, because they are cloaked in legalistic respectability. And once the precedent is set, it is hard to reverse. The danger, say observers, is that disillusioned citizens will lose faith in ballots and turn to bullets.

Still, Déby’s regime is betting that stability will trump outrage. With rebel threats still looming in the north and tensions spilling over from Sudan’s civil war, the government hopes citizens will prefer the certainty of a strongman to the uncertainty of a fractured transition. “People want peace first, reforms later,” one ruling party supporter told local media.

Whether that gamble pays off is another story. Chad’s political history is littered with coups, uprisings, and abrupt power shifts. The Déby dynasty has survived three decades by balancing force and diplomacy, carrots and sticks. But as the younger Déby tightens his grip, he risks overplaying his hand. If protests return to the streets of N’Djamena, the government may once again find itself governing through tear gas and curfews — hardly the image of stability it is trying to project.

For now, Mahamat Idriss Déby is smiling, the ruling elite is secure, and the constitution is pliable. But as every African strongman eventually learns, staying in power is the easy part. Convincing the people you deserve to stay there — that’s where the real marathon begins.