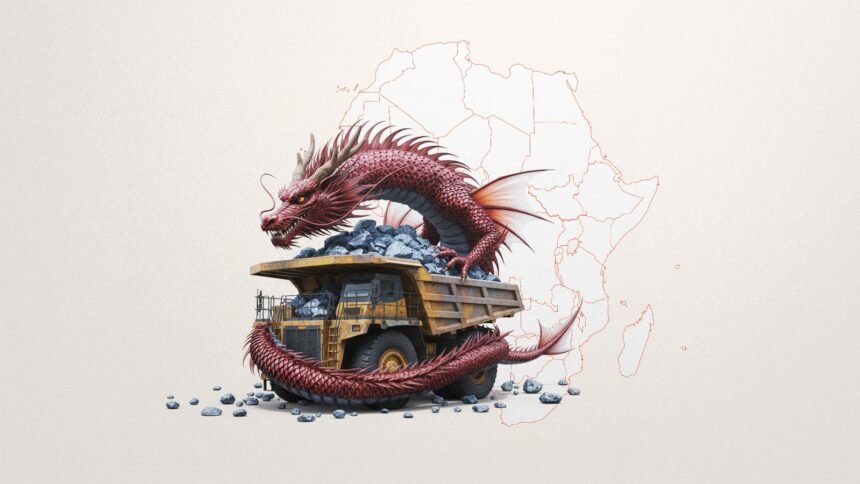

Across the African continent, beneath red-earth plains, rainforest canopies, and mountain ridges, lies one of the world’s most significant concentrations of strategic minerals. Cobalt, copper, lithium, coltan, manganese, platinum, gold, diamonds—resources that power smartphones, electric vehicles, wind turbines, and missiles. For more than two decades, the People’s Republic of China has moved with methodical speed to lock up access to these treasures. What began as a narrative of “win-win” partnership and South-South brotherhood has, in mine after mine, village after village, hardened into a pattern of displacement, labour bondage, environmental ruin, and systemic human-rights erosion on a continental scale.

This is not another story of Western decline and Chinese ascent in abstract macroeconomic terms. It is the story of children with cobalt dust in their lungs, of rivers turned the colour of rust, of sacred hills bulldozed without consultation, of wages withheld for months, of security forces firing on protesters who dare ask for clean water. It is the story of how the world’s green-energy future is being built, in significant part, on an African present that looks disturbingly like the colonial past.

The Long Shadow of Extraction: From Leopold to the Long March

Africa has never been allowed to forget that its subsoil is more prized than its people. Belgian Congo’s rubber terror, South Africa’s migrant-labour compounds, France’s uranium mines in Niger, Britain’s Rhodesian copperbelt—all were chapters in a single, centuries-long volume entitled “Take and Do Not Ask.” Independence redrew flags but rarely rewrote the terms of extraction. State capture, one-party rule, Cold War proxy wars, and structural adjustment ensured that mineral wealth continued to flow outward while poverty, conflict, and ecological collapse flowed inward.

When Chinese state-owned and state-linked enterprises began arriving in force after the 2000 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), many African leaders saw not predators but partners who asked few questions about governance and offered infrastructure in exchange for resources. Loans were extended at commercial rates, roads and stadiums rose quickly, and the language of “non-interference” sounded like respect for sovereignty after decades of IMF and World Bank lectures.

Yet the old logic acquired a new accent. Where European colonisers once used Maxim guns, Chinese firms frequently use debt contracts, private security companies, and the quiet leverage of state power. The extractive model did not end; it was rebranded, refinanced, and turbocharged.

Beneath the Surface: Africa’s Mineral Superpower Status

Africa today hosts:

- ≈70 % of global cobalt production (almost all from DRC)

- ≈50 % of manganese

- ≈40 % of platinum-group metals

- ≈20–25 % of gold

- ≈18 % of uranium

- Vast untapped reserves of lithium (Zimbabwe, Namibia, Mali, DRC), graphite (Mozambique, Tanzania), and rare earths.

In 2024, the continent’s mining sector was valued at approximately US$450 billion and is projected to exceed US$700 billion by 2035, driven overwhelmingly by the global energy-transition minerals rush. The Democratic Republic of Congo alone holds an estimated US$24 trillion in untapped mineral wealth—more than the GDP of the United States and China combined.

The New Scramble: Comparative Investment Landscapes

From 2000 to 2024, Chinese entities committed more than US$80 billion in mining and related infrastructure across sub-Saharan Africa—roughly triple the combined total of the United States and the European Union in the same sector. By 2023, Chinese companies controlled:

- ≈70–80 % of DRC’s industrial cobalt output

- ≈50 % of Zambia’s copper production

- Significant lithium concessions in Zimbabwe (Sinomine, Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt, Chengxin Lithium)

- The largest bauxite complex in Guinea (SMB-Winning consortium)

- Nickel and platinum assets in South Africa, Madagascar, and Burundi

United States & European Union Western investment has surged since 2021 (Inflation Reduction Act, EU Critical Raw Materials Act, G7 Partnership for Global Infrastructure), but remains far behind in volume and speed. The flagship US project, the Lobito Corridor, and EU Global Gateway initiatives emphasise rail, clean processing, and higher labour/environmental standards. Yet they struggle to match China’s ability to mobilise billions of dollars in months rather than years.

Russia’s Russian presence (Wagner/Prigozhin networks, Alrosa diamonds, Norilsk Nickel interests) is opportunistic and concentrated in smaller, high-margin gold and diamond plays, mainly in the Central African Republic, Sudan, Zimbabwe, and Guinea. It is dwarfed by the scale of China.

Fractured Bodies, Silenced Voices: The Human-Rights Catastrophe

Child and forced labour In the DRC’s southern cobalt belt, an estimated 150,000–200,000 artisanal miners—tens of thousands of them children—dig by hand in conditions that collapse regularly. Chinese-owned smelters and trading houses buy this “blood cobalt” through a series of intermediaries, allowing plausible deniability. Amnesty International, Global Witness, and RAID have repeatedly traced cobalt from child-labour sites to batteries in Tesla, Apple, Samsung, and Volkswagen supply chains—all ultimately refined in China.

Violence and repression

- Chambishi (Zambia, 2005): Chinese managers opened fire on Zambian workers protesting conditions, killing five.

- Collum Coal Mine (Zambia, 2010 & 2012): Two separate incidents of Chinese supervisors shooting African workers.

- Bikita Minerals (Zimbabwe, 2022–2024): Villagers beaten and arrested for protesting lithium-mine expansion onto ancestral lands.

- Guinea (2023): Security forces protecting Chinese bauxite interests killed at least seven protesters in the Boké region.

Wage theft and modern slavery indicators. Across dozens of Chinese-operated mines, workers report:

- Salaries are paid months late or not at all

- 14–16-hour shifts with no overtime

- Confiscation of passports (especially for Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and North Korean subcontractors)

- Locked dormitories and fenced compounds reminiscent of 19th-century compound systems

Sexual violence and gender-based harm. Women working as cooks, cleaners, or ore sorters routinely face demands for sexual favours in exchange for jobs or safety. In several documented cases in Zimbabwe and Zambia, managers threatened to blocklist victims’ villages if they spoke out.

Indigenous and land rights. From the Shona sacred hills of Zimbabwe to the Batwa forests of Burundi and the Maasai grazing lands near Tanzanian nickel deposits, Chinese projects have repeatedly proceeded without free, prior, and informed consent, in direct violation of ILO Convention 169 and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Rivers of Poison: Environmental Apocalypse on a Continental Scale

Zambia’s Kafue River (2021–2024). Three major pollution incidents from Chinese copper operations have rendered 120 km of one of southern Africa’s most important waterways biologically dead.

DRC’s Katanga mining province Satellite imagery shows more than 2.5 million hectares of forest cleared since 2000, with Chinese-backed industrial mines and their road networks as primary drivers. Tailings dams leak heavy metals into groundwater that supplies millions.

Guinea’s bauxite plateau. The SMB-Winning consortium has turned pristine forest into a lunar landscape of red dust bowls. Local rice farmers report yields collapsing by 70–90% due to dust and hydrological disruption.

Mercury and artisanal gold Chinese traders dominate the purchase and export of mercury-contaminated gold from Burkina Faso, Mali, Ghana, and Sudan, fuelling a public-health catastrophe that poisons entire river systems.

The Architecture of Impunity: Corruption as Operating System

Chinese mining deals are frequently negotiated in secrecy, signed by small circles of presidential allies, and structured through offshore joint-venture vehicles in Hong Kong, Singapore, or the British Virgin Islands. Signature bonuses, royalties, and tax holidays disappear before parliaments even see the contracts.

Examples:

- DRC: US$6 billion “Sicomines” infrastructure-for-minerals deal (2008) delivered fewer than 15% of the promised hospitals and schools.

- Zimbabwe: US$1 billion+ in opaque lithium deals since 2021, with almost no public disclosure.

- Guinea: US$20 billion Simandou iron-ore project riddled with allegations that hundreds of millions in bribes changed hands.

The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) has repeatedly flagged Chinese companies for non-disclosure, yet Beijing refuses to compel its firms to comply when operating abroad.

Glimmers in the Dust: Resistance and Pathways Forward

Despite the bleakness, African resistance is growing:

- Tanzania’s 2023 expulsion of Chinese cashew buyers who were cheating farmers

- Zambian communities suing CNMC in Chinese courts (a first)

- Pan-African civil-society coalitions such as the African Coalition for Corporate Accountability

- Youth-led movements invoking “No Green Apartheid” and demanding beneficiation and community ownership

- AU reforms: the 2024 Addis Ababa Declaration on Responsible Mining and calls for an African Minerals Fund

The European Union’s 2025 battery regulation, which requires proof of responsible sourcing, combined with US efforts under the Minerals Security Partnership, is finally creating market pressure that hurts Chinese refiners when abuses are exposed.

Toward an African Renaissance in the Depths

The minerals beneath Africa’s soil belong, morally and legally, to its people. They are not Chinese, not European, not American. The continent now stands at a historic inflection point. The same global energy transition that has intensified the rush for its resources also gives Africa unprecedented leverage—if it can collaborate.

A genuinely pan-African minerals strategy would demand:

- Continent-wide minimum environmental and labour standards

- Mandatory local processing and value addition before export

- Public disclosure of all contracts and beneficial owners

- Binding community veto rights over projects affecting ancestral lands

- An African green-minerals sovereign wealth fund to capture and reinvest super-profits

Until such a framework exists, every electric car on a European road, every smartphone in an American hand, and every wind turbine in a Chinese field will continue to carry traces of African blood, sweat, and tears.

The dragon has descended deep into Africa’s mines. Whether it emerges bearing shared prosperity or dragging the continent into a new era of subjugation depends not on Beijing’s goodwill, but on Africa’s willingness to close ranks, speak with one voice, and finally claim the full value of what lies beneath its feet.

The ancestors are watching. The children, coughing cobalt dust, are waiting. History did not end with independence—it is being rewritten, pickaxe by pickaxe, in the depths.