Transatlantic Shadows: America’s Long Game on the Continent

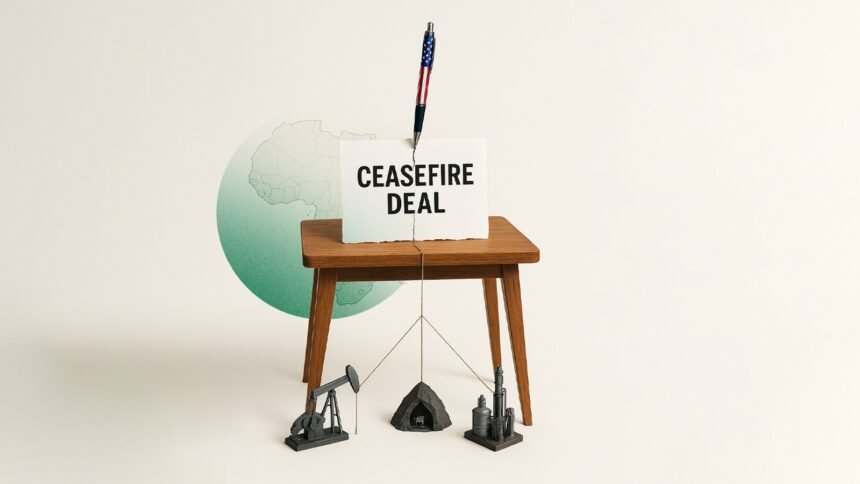

The United States has never approached Africa with blank-slate altruism. From the slave trade through Cold War proxy wars, from structural adjustment to the war on terror, American policy has consistently blended strategic interest with selective humanitarian rhetoric. The second Trump administration (2025 onward) continues this tradition, but with a distinctive accent: everything is framed as a “deal.” Critical minerals for electric vehicles and weapons systems, countering China’s Belt-and-Road footprint, and opening markets for American agribusiness all feature prominently whenever Washington discusses “peace.” In this framework, stopping the shooting is only the opening bid; the real prize comes afterward in mining concessions, port contracts, and preferential trade terms. African governments, desperate for any respite from war, often sign. The deeper work of reconciliation, governance reform, economic redistribution, and climate adaptation is then explicitly or implicitly returned to them, with the African Union expected to carry the load that wealthier powers prefer not to shoulder.

The Art of the Quick Deal: Anatomy of Trump-Era Mediations

Since early 2025, the administration has inserted itself into three major African conflicts with remarkable speed: the eastern DRC-Rwanda-M23 crisis, the Ethiopia–Eritrea–Tigray aftermath, and the Sudan civil war between the SAF and RSF. In each case, the pattern is almost identical—high-level envoys (often family members or trusted business associates rather than career diplomats) shuttle between capitals. Lavish signing ceremonies are staged in Washington or at Mar-a-Lago. Cease-fire language is triumphant and sweeping, yet the fine print on verification mechanisms, disarmament schedules, and transitional justice is conspicuously vague. The deals are celebrated as “historic” and “YUGE” on social media; markets react positively to the prospect of reopened mineral corridors, and within months, most of the agreements begin to fray. Troops remain in forward positions, cross-border raids resume, and humanitarian access collapses again. The White House response is consistent: “We got them to the table and stopped the killing for now; the rest is up to Africans themselves.”

This is not accidental. It is deliberate doctrine: the United States will broker the pause, but it will not pay for, staff, or politically sustain the long peace. That burden shifts immediately to the African Union, to regional bodies such as IGAD and ECOWAS, and, above all, to the warring parties who are now told, in effect, “You own this now.”

Africa’s Unfinished Wars: A Continent Still Bleeding

As of late 2025, Africa hosts at least seventeen active armed conflicts that each kill more than 1,000 people per year. The deadliest include:

- Democratic Republic of the Congo (East): more than 120 armed groups, 7 million displaced, systematic sexual violence, and a shadowy war over cobalt, coltan, and gold.

- Sudan: the army–RSF war has killed over 150,000, displaced 12 million, and triggered the world’s largest hunger crisis.

- Sahel belt (Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger): jihadist insurgencies intertwined with ethnic militias and military coups.

- Ethiopia: lingering communal violence in the Amhara and Oromia regions even after the Pretoria Agreement.

- Somalia: Al-Shabaab stronger than at any point in a decade.

- Mozambique (Cabo Delgado): ISIS-linked insurgency disrupting multibillion-dollar gas projects.

- Central African Republic, South Sudan, Libya: all technically “post-conflict” yet still mired in cyclical bloodletting.

These wars are no longer primarily about ideology or even, in the 1990s sense, ethnicity. They are hybrid wars of criminal accumulation fought by networks that blend militias, regular armed forces, foreign mercenaries, and multinational corporations. Small arms flow in from Eastern Europe and the Gulf; profits flow out through Dubai and Dar es Salaam.

Climate as Conflict Multiplier, Poverty as Recruiter

The climate crisis is no longer background noise; it is the amplifier that turns manageable disputes into existential warfare. Lake Chad has shrunk by 90% since the 1960s, pushing pastoralists and farmers into lethal competition. The Horn of Africa has endured five consecutive failed rainy seasons. In the Sahel, desertification advances 50 km per year in places. When crops fail, and livestock die, young men who have no land, no jobs, and no prospects are easily recruited with $200 and an AK-47. The jihadists, the ethnic militias, and even some state armies all offer the same bargain: fight for us and feed your family.

Extreme poverty (less than $2.15/day) still traps roughly 460 million Africans. Youth unemployment in many countries exceeds 40%. These numbers are not statistics; they are the recruitment pool for every new rebellion. Any peace that does not simultaneously deliver jobs, functioning markets, and climate-resilient agriculture is doomed to be temporary.

Pan-African Vision vs. Persistent Fragmentation

The African Union’s Agenda 2063 and its “Silencing the Guns” initiative remain the continent’s most coherent road map for endogenous peace. The AU has deployed missions in Somalia (ATMIS), the Sahel (G5 joint force, now defunct), and the Lake Chad Basin. It has mediated in South Sudan, CAR, and Ethiopia. Yet the AU is chronically underfunded (only 40% of its regular budget is paid by members; peace operations rely almost entirely on EU and UN-assessed contributions that come with strings attached). Member states routinely ignore AU decisions when vital national interests are at stake. Regional powers (Nigeria, Kenya, South Africa, Egypt, Algeria) compete as much as they cooperate. The Pan-African dream is alive in rhetoric and in the hearts of millions of young Africans, but it remains institutionally fragile.

The AU-UN Hybrid Model: Promise and Exhaustion

Joint AU-UN missions and “hybrid” operations were once hailed as the future. Today, they are exhausted. Peacekeepers die in ambushes they are not mandated to prevent; missions last fifteen or twenty years with no exit in sight; troop contributors grow weary of body bags for conflicts the world barely notices. The UN Security Council can authorise missions, but cannot compel wealthy nations to pay on time or provide helicopters and drones. The result is a slow retreat of multilateral peacekeeping just when Africa’s wars are becoming more diffuse and predatory.

Inclusion or Illusion: Who Sits at the Table?

Almost every Trump-brokered ceasefire has been negotiated by men in suits representing governments or rebel movements led by men with guns. Women, who make up the majority of displaced persons and who keep rural economies alive during war, are rarely in the room. Youth, who form the majority of combatants and victims, are treated as a security threat rather than as partners. Indigenous authorities, religious leaders, and diaspora networks are consulted only for photo opportunities. Durable peace requires that the table be widened, not merely that signatures be collected.

After the Handshake: The Real Work Begins, and Africa Is Left Holding It

When the cameras leave and the presidential jets fly home, the real work begins: collecting weapons from boys who have known nothing but war, rebuilding schools and health posts, restarting trade across former front lines, prosecuting or reconciling atrocities, rewriting constitutions, holding elections that do not reignite violence, and, hardest of all, convincing citizens that the new order will deliver more than the old. None of these tasks is quick, none is glamorous, and none generates headlines that help an American president’s re-election campaign.

That is the crux of the critique: Trump’s Africa policy is not insincere; it is fundamentally transactional. It excels at the theatrical pause, the handshake, the market-moving announcement. It deliberately stops there, because the follow-through is costly, slow, and politically unrewarding in Washington. The message to African leaders is blunt: “We will get you to the ceasefire; you figure out the peace, and if you want our continued goodwill, make sure our companies get the contracts.”

Whether this cold realism forces African institutions to mature, or condemns the continent to another generation of fragile truces followed by renewed war, only the coming decade will tell. What is already clear is that the era of open-ended American nation-building is over. The age of the quick deal has arrived, and Africa, for better or worse, must write the chapters that come after the signature.